How does the world's largest police department balance the security of the spontaneous masses with the freedoms that make us who we are? The counterterrorism cops of the NYPD take us deep inside their extraordinary operation.

The tongues of native New Yorkers land heavy on consonants, and on vowels, too. On words and sentences. On poetry and prose, on dese, dem, and dose. For all the worry that television has homogenized all the fun accents out of existence, the sons of certain neighborhoods in Queens and Brooklyn—they still speak the hell out of all the words. Make a real meal out of them. No posh Manhattan private school diction for these guys, not on your life. And these guys here—these guys are cops, and when they're on the job, people aren't people, they are the more formal in-duh-vi-jew-wuhls, and by the time this man here, Jim Waters, chief of counterterrorism, New York Police Department, gets up the slopes and down the valleys of that word, it's picked up another syllable or two. For reference, Waters sounds a little like the old actor Broderick Crawford, who played a lot of cops. And Waters may be chief of counterterrorism now, but he started out life walking a beat in the 110 Precinct, Elmhurst, Queens, which isn't as quaint as it sounds.

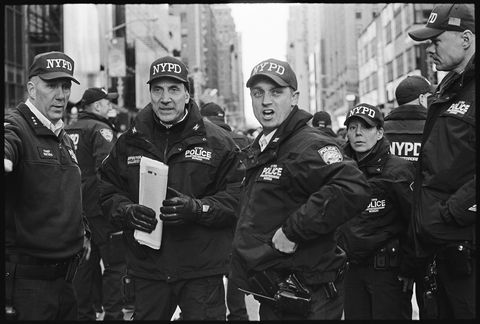

It's just after 2:00 in the afternoon on New Year's Eve, cold dappled sunlight splashes up and down Seventh Avenue, the universe's own spotlight giving God a better look at what in hell is happening down in New York. Everybody, it seems, is curious about this particular spot on the dirty globe today. Chief Waters is standing right in the middle of the street, facing north toward Central Park, keeping a close eye out as the hearties and the crazies and the curious stream from Forty-Sixth Street, take a left toward Times Square, and enter into the "chute" for screening by cops under his command. They're all here for The Show—Midnight in Times Square, baby! hollers a young Asian woman who doesn't look dressed warmly enough at all, as she dances past to join her friends. Chief Waters smiles and nods. His aide-de-camp, Captain Danny Magee, shakes his head, a bemused expression on his face. Magee's always looking to bust somebody's balls.

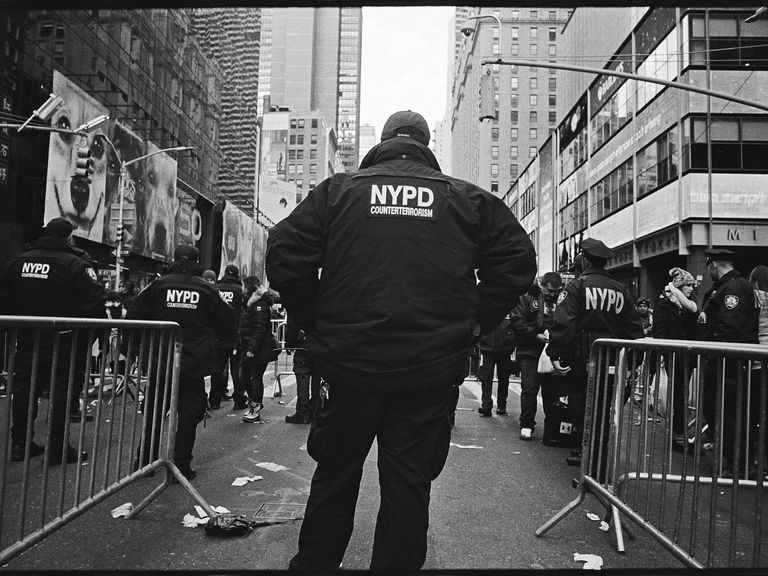

"Some of 'em mighta already had a few," he says. "Once they're screened and in the pens, it's hard to leave and there's nowhere to pee." He pauses, thinks about two million people—that's how many guests they're expecting tonight—with no place to pee. "They're gonna need a jar!" he says, his face erupting in a crinkly smile. If Waters is Broderick Crawford, Magee is more Jimmy Cagney. Very Brooklyn, total wiseass. Mother, wonderful woman, still lives in the house he grew up in. "Maybe a friend can hold up a sheet, so they can take turns using the jar! 'Cause they're gonna need a jar." You cannot spell jar the way Magee says jar. His voice is snappy and he is shouting a little because this intersection—Forty-Sixth and Seventh—is madness, the center of an enormous mobilization of a security apparatus that has no peer anywhere in the world in terms of civil police departments. In the name of fun and freedom of assembly, seven thousand cops are at this moment being deployed to harden a grid in the center of Manhattan between Thirty-Eighth Street and Central Park, and between Eighth Avenue and Sixth Avenue. As mass gatherings of the public go, this is the big enchilada, the Super Bowl. A couple years ago, incidentally, the city hosted an actual Super Bowl at MetLife Stadium across the way in Jersey—Chief Waters threw that party, too. "That's all we are—party planners," says Magee. "Party planners with big guns and a bomb squad." Waters smirks. "That's why we keep Danny around," he says. "For his sense of yuma."

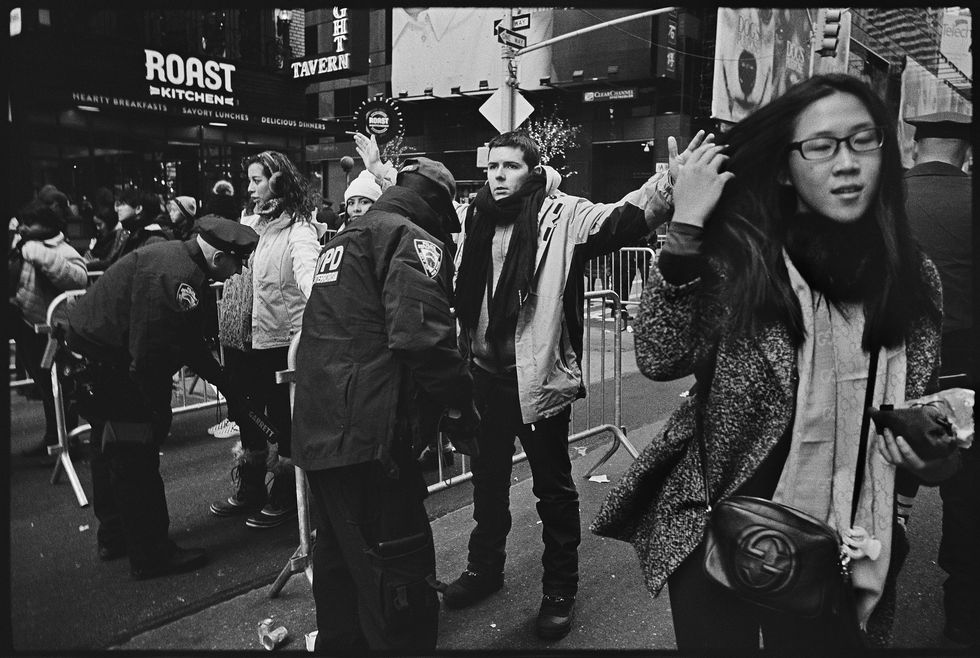

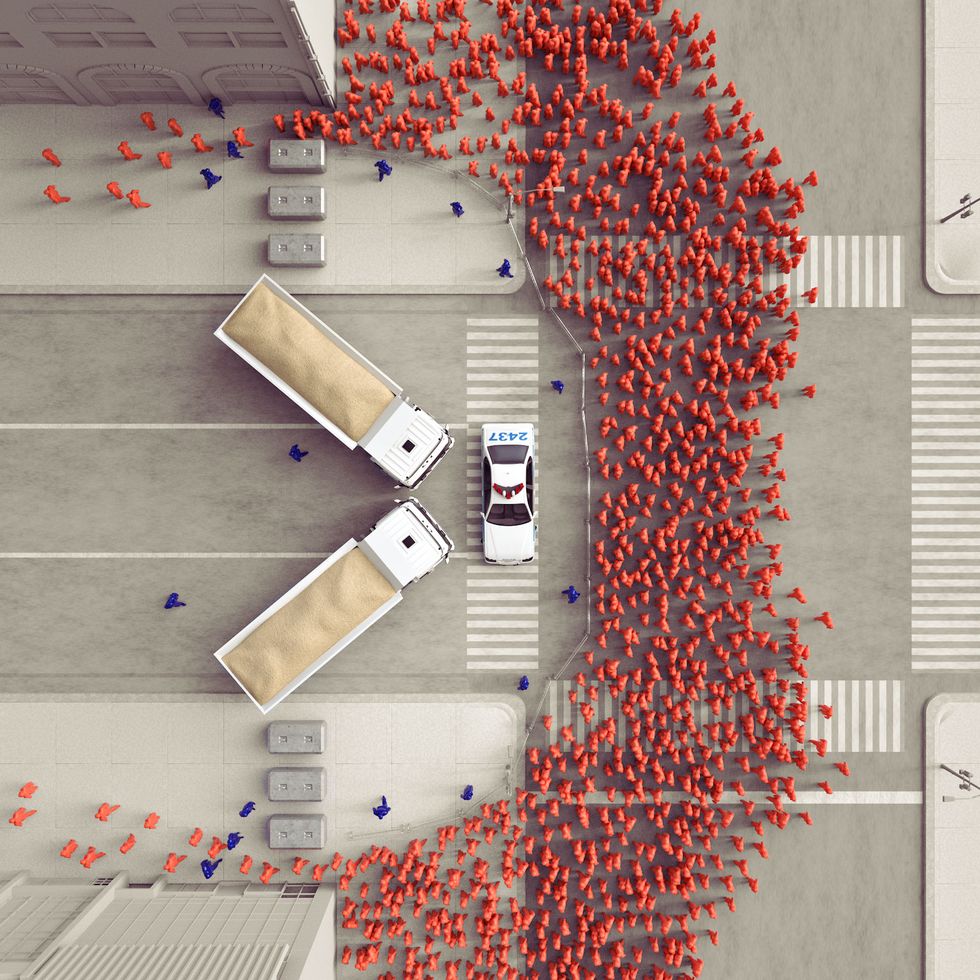

It's not just Magee. Everybody's in pretty good humor today. The pizza guy on the block is sending a platoon into the jovial crowd with fresh hot pies. "Thirty bucks!—that's a helluva markup," says Magee. "He's making his nut for the year today." But he sure is keeping them fed in the pens. Waters says there are forty-eight of the block-long enclosures, from here all the way up toward the park. They were erected by hundreds of cops using thousands of metal barriers starting at midnight last night. Any brave souls who want to watch the ball drop are entering the grid from the east and west, and at entry points on either Sixth or Eighth avenues, they subject themselves to a handheld magnetometer that detects any ferrous metals, and maybe a pat down, a radiological detection test, random explosive-trace detection in which something that looks like litmus paper is wiped on their hand or run down the length of the zipper on their jacket, and everybody gets sniffed by a dog. They then will walk toward Seventh Avenue or Broadway, past at least one twenty-ton sand truck, two on the wider streets—each topped off with another fifteen tons of sand—blocking the street, past the row of six-foot-long, two-ton concrete blocks blocking the sidewalk. Counterterrorism cops have to pay attention and learn from what's in vogue among people who want to kill as many people as possible, and this year's innovation in mayhem has without doubt been driving a big truck into as big a crowd as possible. So today, Waters is hardening the perimeter of the grid with trucks so heavy that "ain't nothing gonna move 'em," but that have the added convenience of being portable, so at the end of the night you just drive them away. Down the block the once-screened stream of humanity goes toward the pens. They walk, silly hats on and bottled water in hand, and when they reach Seventh Avenue, they run into Chief Waters and his boys and are screened all over again. Two million people, screened twice. Magnetometer, radiological, dog. All the while, "red cell" teams of cops in plainclothes are dispersed among the crowd, trying to breach the system, probing its vulnerabilities, and "that bag can't come in here, ma'am. Ma'am, no bag," Magee says. "What's that? You can either walk out the way you just came in, or you can donate it to our growing bag collection here." Magee pulls back a tarp to reveal bins and bins of bags of all shapes and sizes and degrees of fanciness that have already been surrendered. A young woman, thinking better of the whole idea, is clawing deep into the bin to retrieve a bright-green leather bag to be on her way.

Captain is an old-man rank, a retirement rank, and Magee isn't yet forty. Probably ought to pay attention to that name, he's going to be somebody. Waters is on the verge of fifty-seven, and with compulsory retirement coming when he hits sixty-three, he is both state-of-the-art in counterterrorism and nearing the end of his career in counterterrorism. He's been pulling New Year's Eve duty since infancy—

"I remember, I was a young sergeant, '86 I think it was. Forty-Seventh and Seventh, and they told us to bring our hats and bats—riot helmets and nightsticks. That was about the height of technology at the time. I had ten cops and by 7:00 or 8:00 p.m., the crowd was already somewhat, uh, intoxicated . . ." Not to mention completely unregulated, and somewhat aggressive. Bottles were flying, and so Waters told his men to put their chin straps on. One of his cops wouldn't do it, and a couple minutes later, he took a bottle to the head, knocking his helmet sideways. "I said, Are you gonna put your chin strap on now?" The threats were different then—FALN (militant Puerto Rican nationalists) and the like—but nobody really knew yet what counterterrorism was, or why it might be necessary.

A black Lab at the end of a cop's leash brushes your leg as he methodically pushes his way through the crowd, padding spryly back and forth across the avenue. That's Kevin, one of the department's vapor-wake dogs. German shepherds are very good at sniffing a bomb in a backpack stuffed under a mailbox, but these Labs, specially trained at Auburn University, are expert at moving targets. As each of us moves through the world, we constantly displace air, disturbing a universe of molecules, and it is the plume of air left in the wake as each reveler cuts through the space in front of him that Kevin is sniffing, in patient search for precursor bomb material or radiological matter of any kind. We give off molecules, and so do bombs. Once, during a half-marathon in the park, one of the Labs alerted on a runner wearing only shorts and a tank top, and was insistent that there was something suspicious on the man. "Excuse me, sir, are you undergoing radiation treatment of some kind?" The dogs sometimes alert on cancer patients. The man dug into the pocket of his shorts, and brought out a tiny pill. Nitroglycerin. Somebody had told him that taking one halfway through the race turbocharges you for the second half. The vapor-wake dog had discovered his secret.

To secure the grid for tonight, forty of the NYPD's dogs are on the job, including eight of the vapor-wake Labs. Magee says that the department favors the Labs, both for their extraordinary skills but also because people sometimes have negative associations with shepherds. Labs aren't as intimidating. Regardless of breed, all the counterterrorism dogs are named after a fallen cop. Kevin is named after Kevin Gillespie, a street-crimes cop who was killed on the job in 1996. And here comes Vin, named after Vinnie Danz, an emergency-services cop killed on 9/11.

Waters plans to spend all afternoon in constant communication with his officers deployed around and throughout the grid, making certain that this massive undertaking that has been in planning for the past 364 days is proceeding smoothly. He'll be traveling back and forth to the Joint Operations Center at 1 Police Plaza downtown, the nerve center of all police operations but especially, today, counterterrorism and intelligence, which will be collecting information from NYPD assets stationed in thirteen foreign countries, including most of the current hot spots. He will be looking at those thirteen countries as they go to midnight, like dominoes heading to New York. If midnight passes without incident in London, Tel Aviv, and Istanbul, Waters will breathe a little easier. He knows and has staked out every parking garage in the grid, to make sure no bad guys go in to plant something, or out, unscreened, to do harm. Two days ago, he had every manhole cover in the vast swath of midtown Manhattan marked, a job so big that it alone would strain the ability of most other cities to do it. The checklist of all that Waters and the seven thousand cops deployed here today have to do reels in his head. You can see it. He is buttoned-up but cordial, talking easily one second and lost behind his eyes the next. But look around today and you are likely to find Chief Waters, given a spare moment, down on the ground—or in this case, kneeling on the street—playing with a large variety of dogs, all of whom are official New York City police officers, wearing shields and signs that read "Do not pet."

Just then, an interloper with brown hair and glasses—with a look of determined nonchalance—gets through these layered and concentric circles of security wearing a backpack, walks right on through, and after screening his share of approximately five hundred thousand people so far today with nothing so much as a false positive on a bologna sandwich, Vin goes nuts. He strains at his leash so hard he almost pulls his partner off his feet. Vin points at the object of his concern with his snout, almost touching the backpack on the man's back, and then he sits on his haunches, supremely alert. The man is now frozen in his tracks. "You know it's a definite hit when the dog sits down," Vin's partner says. "These dogs do not make mistakes." Vin has alerted on a decoy, a test of the system. The guy with glasses was let through on purpose, and in his backpack he carried a half-pound of smokeless powder that Vin could smell from here to tomorrow.

Magee taps his watch, and now Waters is up again and moving, heading to Forty-Second Street, past pen after pen, full of the most joyful revelers with the greatest bladder control you ever saw. Everywhere he walks, officers stop and salute. They're not used to seeing a three-star on the job on a day like this—maybe for the ball drop, but not working. He is congenitally modest and is always trying to deflect attention from himself to "more deserving people, the men and women of the NYPD." He has eyes that droop slightly, hair high and tight, and lumbers along like a workingman. As he passes a young woman up against a barrier with some friends, she sees him and says, a little sleepily, "Thanks for protecting us . . ." she slowly leans forward to read the name on his jacket . . . "Waters." Her arms are crossed tight and she has the sleeves of her sweater pulled down to cover her hands. She looks up at him and smiles a rheumy smile.

"You look cold," Waters says.

"Oh, I am not cold, believe you me," she says right back.

"Well, have a great time tonight," he says, and he's off.

A few steps away, his smile gone, he's all business. "I am not worried about a nuclear device going off here tonight," he says. "We know well the capabilities out there, and I'm confident that's out of the question. What I am worried about is the lone wolf that we don't know, that we can't know. The ISIL model now is to say, Act where you are, with what you have. That's where the Nice and Berlin Christmas market truck attacks came from. So I'm worried about that guy." He walks on, picking up his pace toward Forty-Second Street. "But we don't worry. We act. That's what everything you see here today is all about."

Waters has been chief of counterterrorism since 2008, running a select division of one thousand cops. Before that, he was head of the Joint Terrorism Task Force for five and a half years. It's been all terrorism all the time since shortly after September 11, 2001. Before 9/11, there was no counterterrorism at the NYPD. So it's kind of his baby. That's the kind of duty that is impossible to leave at the office. And so he's got a hyper-vigilance that just won't quit, he doesn't sleep much, and when he does sleep he is frequently awakened in the middle of the night with news of the world that ripples all the way to New York, all the way to his bed on Long Island. And then he's up for good. "Chief hasn't had a decent vacation in like, ever," Magee says, laughing. "His poor wife, you know?"

"Oooh, my wonderful wife," Waters says. "Sometimes we just can't catch a break."

One Saturday night last September, Waters had driven into the city to pick up a couple of suits that he'd had tailored, and "I said to Joanne, C'mon, we'll go to dinner. There was a place in Brooklyn that she liked." No sooner had they gotten on the Williamsburg Bridge than a job came over the radio. Didn't sound like much at first, but Waters knew he had to listen to it. Traffic was light going to Brooklyn but terrible coming back to Manhattan, and by the time Waters and his wife got to the other side of the bridge, "Uh, ya know, the first units were on the scene, and they were calling for ambulances." A bomb had gone off on a random block in Chelsea. The United Nations General Assembly was in town, 120 heads of state, and they picked Twenty-Third Street instead.

Waters made a U-turn, told Joanne, "Hold on. If you have to close your eyes, close your eyes," and he floored it, weaving in traffic back across the bridge, lights flashing. He was on the scene in ten minutes, pulling up just behind the bomb squad. He parked his truck, and walked up, trying to absorb the extent of the damage, trying to get an assessment of the number of injured, looking for secondary devices, which was at the top of his checklist that evening as he approached. "Seeing a first sergeant, I said, 'What are we doing?' I wanted to see what he says. 'We're doing a search for secondary devices.' That was music to my ears."

That's the constant drilling to these guys: Second devices target first responders. Assume there's a second device, and find it.

And then of course there's the technology. The NYPD has three thousand cameras of its own all over the city, and access to seven thousand more through partnerships with private businesses. From a command center downtown, they can even activate and turn the cameras to the desired view, or consult footage from thirty minutes or three hours or three days ago to get a clear picture of the who and the what. Because of a program called the Domain Awareness System, and software developed between the NYPD and Microsoft, all of these video resources, as well as data on all ongoing and active calls and a database of what is known about previous police interactions with any given address in the city, are instantly available to all thirty-six thousand NYPD cops—on every desktop and on thirty-six thousand department-issue Nokia Windows devices that each cop carries in his pocket. DAS has revolutionized policing. Now, when there is a domestic violence call, no cop has to go blind into the situation—he or she knows instantly of previous calls at that apartment, whether there are outstanding warrants, whether there might be weapons present, or whether there is no history at all. That technology can save lives on both sides of the door.

And then, hallelujah, within two hours of the first call, cops found that second device on Twenty-Seventh Street. The news reports had gone out about the explosion on Twenty-Third Street, and Waters cautioned the investigators to make sure it wasn't some kind of copycat device. "We play everything for real, and as soon as I got there, the fellas said, 'No, it's real.' I can't say enough about the courage and focus of the bomb squad guys."

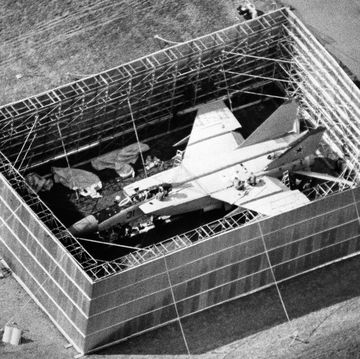

It was a pressure-cooker bomb, in the mold of the Tsarnaev brothers' work in Boston. It was carefully removed to the outdoor range, at Rodman's Neck, in the Bronx, to be taken apart and rendered safe. They pulled up the Total Containment Vessel, which is a vehicle that is so armored that if you sealed the device inside and it detonated, you wouldn't hear it. But the trick, of course, is getting the device inside the vehicle. At the scene, the bomb squad removed the phone—which was designed to be used as either timer or detonator—from the pressure cooker. Then with a robot, cops remotely brought it to the TCV. There's a basket inside, which hangs on a couple of sturdy straps, and a cop with a joystick placed the device into the basket so that it was suspended and would be able to move with the motion of the vehicle without bouncing around too much. And here's the tricky part, because once it's in the basket, then a bomb-squad technician has to put the suit on and go close that door. So for that thirty seconds, he's in very close proximity to that device. Call it a bomb. And one of these has already exploded, injuring dozens of people. He locks the door. Good. Now if it explodes, it explodes, there'll be no danger to anyone. Drive it up to the Bronx, and go through all those steps in reverse. Then take the device to the pit area, which is surrounded by three walls of blast-proof concrete block that go up about fifteen feet and is open on the fourth side. Hard ground, steel workbench, industrial vise on the end. Here, they practice with an identical pressure cooker. How are we gonna do this? Dry run after dry run after dry run, to get comfortable. Time for the real pressure cooker. They first try to open the lid, which doesn't work, so, using "a couple of bomb-squad techniques," they pop the lid off. Now what? It could explode, which wouldn't be good for the preservation of evidence and the invaluable forensic analysis. But because of the care the professionals took, it didn't explode, and the FBI evidence collection guys had, ya know, a perfect crime scene, if you will. They had the pot, they had the lid, they had all its contents, perfectly preserved. All of the evidence they could want. Not only for the trial, but to study, learn from, and defend against the next attack.

It's a pretty elaborate deal, a messy, sprawling civil society of eight million of the loudest, most opinionated people, all with freedom to move and assemble and protest and express themselves and push and test the limits of what is acceptable as their birthright, because "that's what makes 'em Americans and that's what makes 'em New Yorkers," the chief says. And it's his job to let 'em express and assemble and scream to their heart's content, and be safe doing it. And now there's a president of the United States who has a building or two in his town, and a lot of the guy's neighbors seem to want to regularly demonstrate their appreciation by showing up at his door by the hundreds of thousands and giving him the old Bronx cheer. Why, the United States has suddenly entered into a new era of such mass gatherings, both planned and spontaneous, often both at the same time. Like when you're expecting sixty thousand for the Women's March up Fifth Avenue and four hundred thousand show up. "Ha!" the chief says. "It never does get boring!"

Now Waters is standing at ground zero for tonight—Forty-Second and Seventh—and the light is changing as the afternoon accelerates and the checklist is scrolling behind his eyes. Two days ago, in the police commissioner's executive command center, Commissioner James O'Neill's executive staff had run through the plan for New Year's Eve. The command center is a conference room that looks just the way it would look in the movies—all blacks and grays, leather and marble, the walls covered with screens and data and images from all over town and all over the world. Whaddya got? Commissioner O'Neill said, taking a seat at the head of the table. And one by one, the executives ran through a list of plans and assets and allocations that would compare decently to the landing at Normandy:

Five Joint Terrorism Task Force response teams; the bomb squad is broken down to four response teams within Times Square alone, with additional response teams to cover the rest of the city should something happen; somebody remember to thank the sanitation commissioner for the sand trucks; gotta seal the manholes, check and double-check that, yes you; five ballistic vehicles spaced out strategically; large tactical harbor unit for interdicting and boarding a boat or boats, accompanied by SWAT team, prepositioned and ready to go; ten prepositioned light trucks in case there is a blackout—enough to illuminate all of midtown Manhattan so people can see to move around safely, no panic; ten observation teams positioned on high ground—made up of two cops, one to observe, one to communicate, with a "sniper component," with corresponding response teams on the ground; armored vehicles on Forty-Sixth and Forty-Second, with tactical-weapons component, to neutralize anything serious at Times Square; "Archangel" team, a.k.a. "the Holy Shit" Package (this consists of an REP—emergency services truck, WMD team, canine team, light truck, Total Containment Vessel, a BearCat armored truck in case you have to roll into a raging gun battle to rescue people, that's the thing you're gonna use, WMD response trucks, two vapor-wake dogs, seven EDCs [explosive detection canines] and six patrol dogs); air-sea rescue at HUSH [Harbor Unit Station House] on the Brooklyn side, with helicopter and divers standing by, because if the assault starts with them shooting at one of those party boats in the harbor, that's not the time to think about how are we gonna get resources out to them; a Hazmat/chem/bio team stage on the East Side with quick access into and out of Forty-Second Street; gotta implement flight restrictions below 110th Street, nothing under four thousand feet; seven harbor launches in harbor ready to respond, and four harbor launches doing Staten Island ferry escorts; Hostile Surveillance Teams [plainclothes cops at eight critical subway stations in midtown, wearing the funny hats but looking for hostile surveillance]; new emergency-vehicle routes designed; new radio frequencies for everything . . .

Captain Magee interrupts the reverie. "We have to get downtown," he says. "To the JOC." That's the Joint Operations Center at 1 Police Plaza, the war room of coordinated interagency activity on any night, but especially tonight. "Yeah, yeah," Waters says. "I'll be right there."

There is a profound tension to this work, and a sobering recognition that in an open society you can only ever be so secure. A police state might be perfectly secure, but no one with will or imagination would want to live there. The roiling civic conversation of our time has been about the opposing demands of security and freedom. And that is the seam that Chief Waters works, very sensitively. All of this—the vast array of police assets deployed to both project power to the bad guys watching—they're always watching—but also as lightly as possible so as not to unduly burden the people they are serving—is being done with the ultimate goal of . . . absolutely nothing happening. A good party, and that's it. So that at twenty seconds to midnight, as the countdown proceeds and the crowd noise suddenly doubles, a guy says, "Go confetti," and on that word, 120 people high on top of seven buildings encircling Times Square will begin to drop three thousand pounds of two-inch-by-two-inch pieces of colored tissue paper, one handful at a time, and the paper will float up on the frigid air of the vortex of the high-rises, swirl around in thick clouds before snowing back down to earth, landing on the shoulders of the tactical units with their long guns, and landing on the head of a little girl, who will squeal, "I can't see, it's so much!" and landing silently on the ground of the grid, the only unscreened and unscrutinized objects allowed anywhere near here all day.

And Mayor Bill de Blasio and his beaming wife will make a beeline for Waters and bend down slightly to shout, "You did it! Great job!" and clap him on the back, and the secretary general of the U.N. will nod and smile, and the governor, and the secretary of Homeland Security, and various celebrities. All deeply appreciative for all that goes into having absolutely nothing happen. Grateful for the herculean task that goes into making a quiet night.

Waters heads to his car. There's a ton to be done before then.

Seven hours to midnight.

find typically that the more money I make, the smaller my office is."

That's John Miller talking. He is the deputy commissioner of the NYPD for Intelligence & Counterterrorism and former broadcast journalist who could well be the only cop in the world whose ride-along partner was once Barbara Walters. "In TV, my office was usually just a glorified cubicle." He has a pretty big office right down the hall from Waters's, in the unbeautiful suite of offices that make up the eleventh floor of 1 Police Plaza, the city-state that houses the administration of the largest municipal police force in the world. "My own army," former mayor Michael Bloomberg once called it.

Miller is also probably the only cop who has a picture on his office wall of himself with Osama bin Laden—from 1998, at bin Laden's hideaway in Afghanistan, the last time an American journalist interviewed the terrorist. In 2011, after an American SEAL team killed bin Laden, Miller was in the top-secret CIA briefing with Director Leon Panetta, and at the end of the briefing Panetta said, any questions? "I'm like, uh, did he say anything? Like when they confronted him on the stairs, was there any dialogue? And he laughed and said, There wasn't a lot of conversation. I thought, Excellent, so I actually still do have the last interview with Osama bin Laden." There are many other pictures in the office—Miller with the pope, with President Obama. He keeps his Emmys elsewhere. All of which testifies to the utter bizarreness of Miller's career—which spans from calling in news reports to local New York TV stations from his bike in the early seventies, to being the authority on John Gotti and the mob in the eighties, to a first foray in law enforcement in the mid-nineties, to hopscotching back and forth ever since—from NBC and ABC, cohost of 20/20, to Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman, to 9/11, when he sat by Peter Jennings's side for sixteen hours calmly explaining global jihad to a stricken country, to going to work for the FBI and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, to now overseeing the strategy and mobilization of police resources to protect any self-respecting terrorist's bucket-list target city—you can get whiplash just reading Miller's résumé.

When Popular Mechanics contacted the NYPD to ask about how police design security for mass gatherings in the age of terrorism, it was Miller who said, "Talk to Chief Waters." But the same skills that made Miller a good reporter—taking in information, synthesizing it, telling you what it means—have made him sort of a philosopher king on the subject, too.

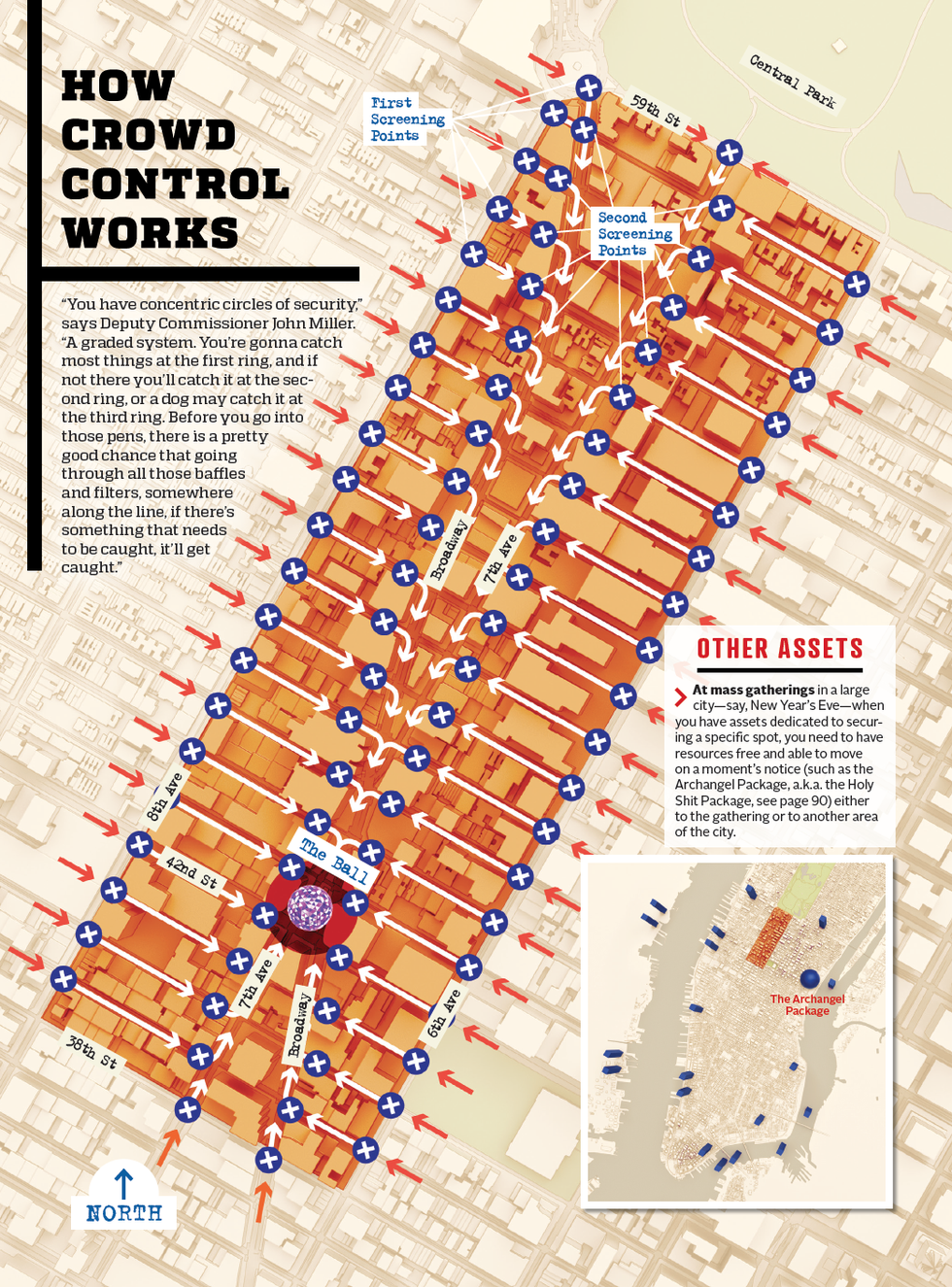

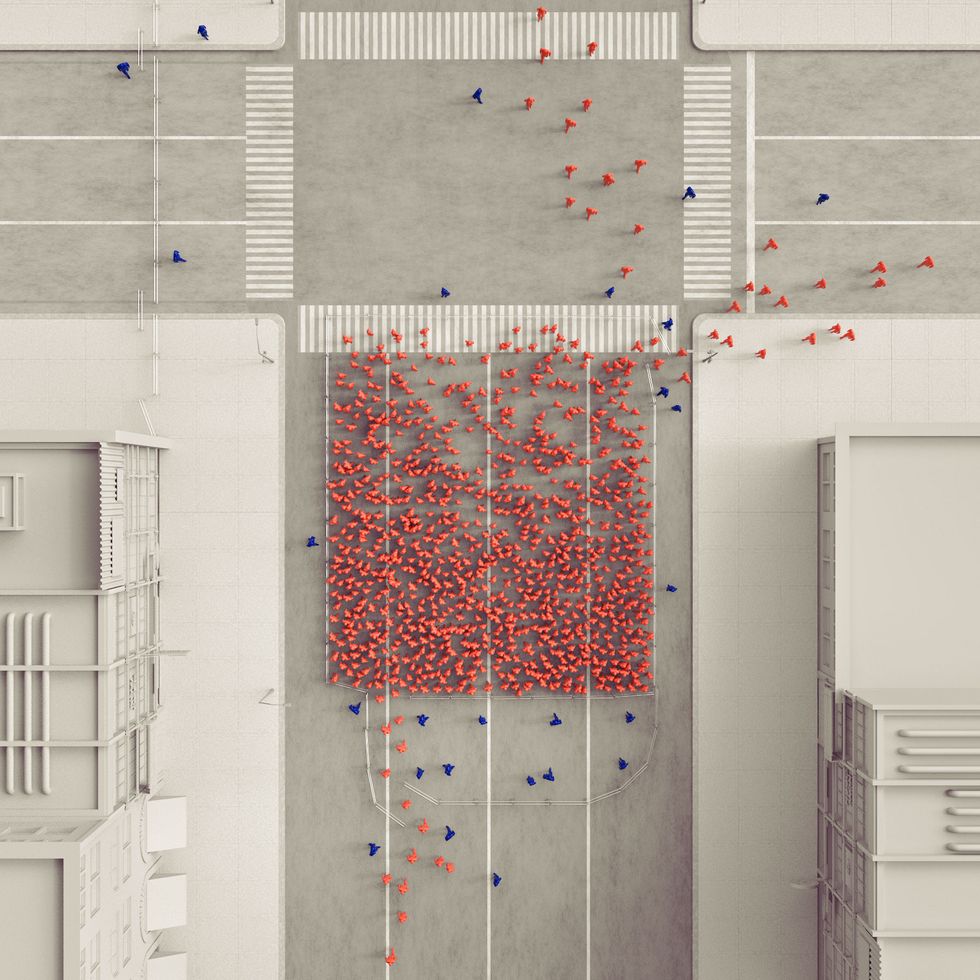

"You've got New Year's Eve, where you have concentric circles of security," he says, "on the idea that you can't let a million people in and have total security. So you've got to have a graded system. You're gonna catch most things at the first ring, and if not there you'll catch it at the second ring, or a dog may catch it at the third ring. Before you go into those pens, there is a pretty good chance that going through all those baffles and filters, somewhere along the line, if there's something that needs to be caught, it'll get caught. But that's about the event. When you design a mobilization for New Year's Eve, with extraordinary assets pointed at a single spot, you also can't take your eye off the rest of the vast metropolis outside of your grid. You can't have all your assets tied up in one place. There's the whole rest of the city out there."

What police learn from so many of the recent events around the world is that the attacks come where the security isn't. "Take Orlando," says Miller. "Where is the counterterrorism package in Orlando? It's focused on Disney. That's where the concentric circles of security are. But the single largest loss of life in a terrorist incident on American soil since 9/11 occurred in Orlando, but not at Disney. It was miles away, at two o'clock in the morning, in a nightclub, on Latin night. So you can do all the targeting and analysis about where you should put your resources, but there is a randomness to these things, and we have to prepare for randomness, too."

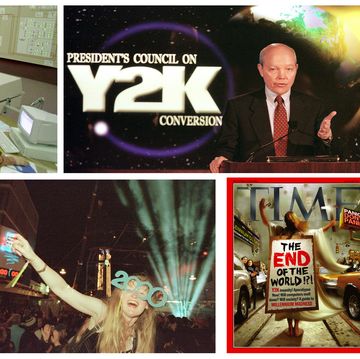

So if you apply that thinking and these "security overlays" to New Year's Eve and Times Square, what does randomness look like? In the great feedback loop of the universe, as the clock ticks down to midnight, and the pens fill up and the air gets colder and millions of people mill about in the charged atmosphere, NYPD executives, with their checklists being checked and rechecked, get their answer.

Five thousand miles away, at 1:14 a.m. local time, at a nightclub in Istanbul called the Reina, randomness happens. A gunman opens fire with a Kalashnikov at people dancing, drinking, and laughing in the new year, slaughtering thirty-nine of them before disappearing into the night. Within minutes, as help is still on its way, the mobile device on Jim Waters's belt starts pinging.

He was about to get a bite to eat, for chrissakes, but no time for that now. In a situation such as this, a man in Waters's position has to grab the analyst in his office and find out as much good information about the circumstances and target in Istanbul as he can, quickly, and then consider soft targets in his own city that might be similarly vulnerable, all while hosting a party for two million guests. Tonight is busier than last year, could be a record. By 8:00 p.m., the pens are filled all the way up to Fifty-Fifth Street, thirteen blocks north of Times Square. "You can't even see the ball drop from Fifty-Fifth!" says Captain Magee. "But you can hear the roar of the crowd I guess, feel the vibrations, say you were there."

With the news from Istanbul, the executives at NYPD in charge of counterterrorism can feel another, unwelcome vibration. There are nightclubs too many to count all over New York City, in all five boroughs. But if there is a disaffected guy out there, Chief Waters's lone wolf, who has been thinking about making his mark but maybe has doubted his abilities or has hesitated for some reason, and he sees the news from Turkey and finds in it his inspiration to impulsively act, where would he go? When would he go there? How would he maximize the statement he's trying to make?

"There are neighborhoods that compare to the neighborhood in Istanbul," Waters says. "Concentrations of nightclubs and restaurants, active street life. The Village all the way up the West Side, Chelsea, the Meatpacking District. We haven't touched a single asset for New Year's Eve, haven't pulled and won't pull anything out of Times Square. Everything will remain here as it is. But we are directing available tactical units with long guns already on for the 4-to-12 shift to circulate in the area—up to a dozen cars—they'll leave their guns in the trunk for now, don't want to alarm people. Just establish contact with proprietors, let them know they're there. Be seen. Establish deterrence. Put people at ease so they can have a good time. Ten, fifteen minutes at each place—now you see us, now you don't. Move on to the next one, then come back. Over the course of an hour they'll be in four or five locations."

One more tactical ball in the air for Waters and his cops to juggle. One more jolt of adrenaline to propel everybody toward tomorrow. As the crowd and the colors swirl around him, as Mariah Carey struts the stage right over there not singing, the chief of counterterrorism is on the phone constantly with all of his executive staff, getting one-minute briefs from all sectors and levels of responsibility for the grid. He smiles. "The way I work is, I know if they say, 'Everything's great, chief, no problem,' I know I'm not getting the truth. Either they aren't doing their job, or they've already corrected a problem and feel like they don't want to bother the boss. That's policing—situational awareness and constant adjustment to conditions on the ground."

Waters and his coterie are in motion and remain in motion, making their way back and forth through the clotted blocks at the heart of Times Square, checking with lieutenants, detectives, inspectors, there's Commissioner O'Neill over there talking with the press, and Mariah Carey again—"she walks through like she's the Dalai Lama or something," Magee cracks, "eats up resources, but that's okay, it's part of why everybody's here"—and the music is loud and man, Ryan Seacrest wears a lot of makeup, and the empty zone right in front of the ball begins to fill with cops, and three hours collapses in an instant.

Midnight is upon us. Further uptown, near Central Park, the magnetometers and the dogs are still working as the stragglers get screened, and the semi-official position of the New York Police Department might be described as lighthearted vigilance. Jubilant wariness.

Joanne would normally be here for the ball to drop, but she's running the midnight 5K up in the park tonight. Chief Waters checks on the security for the run, then makes a last call. "How are things in Chelsea? Quiet? Good." He hangs up, slips his phone into his pocket, and is quiet for the first time in hours, amid the roar at the crossroads of the world.

One minute to go.

In his head, he's getting to the bottom of that checklist. "Now is when I always call my muthah," Captain Magee says, turning away to talk on the phone. Waters smiles. "I know his mother," he says. "Wonderful woman." He is still smiling when his eyes suddenly get cloudy. "I lost my mother this year . . ." he says quietly. He turns away for just an instant.

Thirty seconds.

He turns back, all business again. Checks his watch. Looks up at the ball. "You know, the most important thing for us to remember," he says, "is that we are a free society, and we do our job well when people are as free to move and as safe as possible doing it ."

Twenty.

"You can't protect everything all the time, or you actually protect nothing."

There is a sign Waters keeps in his office. Reads it coming and going, every day. "Did you do everything today to prevent an attack tomorrow?" it says.

Here we go.

10 . . .

9 . . .

8 . . .

SCREENING

For a controlled event (as opposed to a more spontaneous exercise of free speech) of two million people, screening is essential, as is blocking access to where the largest concentrations of the crowd will be assembled. In addition to the street being blocked by fully loaded sand trucks, the sidewalks are blocked by two-ton concrete blocks.

PENS

Back in the old days, New Year's Eve in Times Square was an unsecured, alcohol-drenched free-for-all, which, in a post 9/11 world, is simply unheard of. Now, following screening, the secured revelers are congregated in "pens," less free to move, but less likely to get hurt.

This story appears in the April 2017 Popular Mechanics.