The U.S.-Canada Border Runs Through This Tiny Library

One of the only libraries in the world that operates in two countries at once.

Rumor has it that the 18th-century surveyors who drew the official line between the U.S. state of Vermont and the Canadian province of Quebec were drunk, because the border lurches back and forth across the 45th parallel, sometimes missing it by as much as a mile. But the residents of the border towns didn’t particularly mind, mostly because they ignored it altogether

For around 200 years Derby Line, Vermont, and Stanstead, Quebec, essentially functioned as one town. Citizens drank the same water, worked in the same tool factory, played the same sports (primarily curling), fought in the same world wars, and were born in the same hospital in nearby Newport, Vermont. They also shared the same cultural center, the Haskell Free Library and Opera House, an ornate Victorian edifice built deliberately on top of the international border in 1901 by the Canadian wife of a wealthy American merchant.

In the last several years, though, the common culture of the two towns has been eroded, largely due to the increased emphasis on securing the U.S. border in the years following 9/11. Gone are the days when a local resident could walk across the dividing line with a smile and a wave. But against all logic, the Haskell Free Library and Opera House continues to serve both Vermonters and Quebecers, and remains a transnational space that residents from both the U.S. and Canada can enter without a passport. Today, it is one of the only libraries in the world that exists and operates in two countries at once.

When Martha Haskell decided to build an elaborate, turreted, neoclassical building out of local granite and brick, the plan was for the second floor opera house to fund the first floor library. She went all out for the opera house: elegant painted backdrops, plaster cherubs, tin ceilings, a carved balcony, a painted curtain depicting Venice, and a proscenium arch with gold filigree. At the time, entertainment-starved Vermonters would happily travel many miles through all kinds of weather to see a show.

Of course, Haskell couldn’t have predicted the advent of moving pictures, which immediately cut into opera house profits, and so the Opera House has limped along for nearly a hundred years, supported by the more modest public library below it. But committed devotees have kept it alive, and during the summer season you can still catch a show or listen to live music. Most of the seats are on the U.S. side, though, so in all likelihood you’ll sit in America and watch performers located in Quebec.*

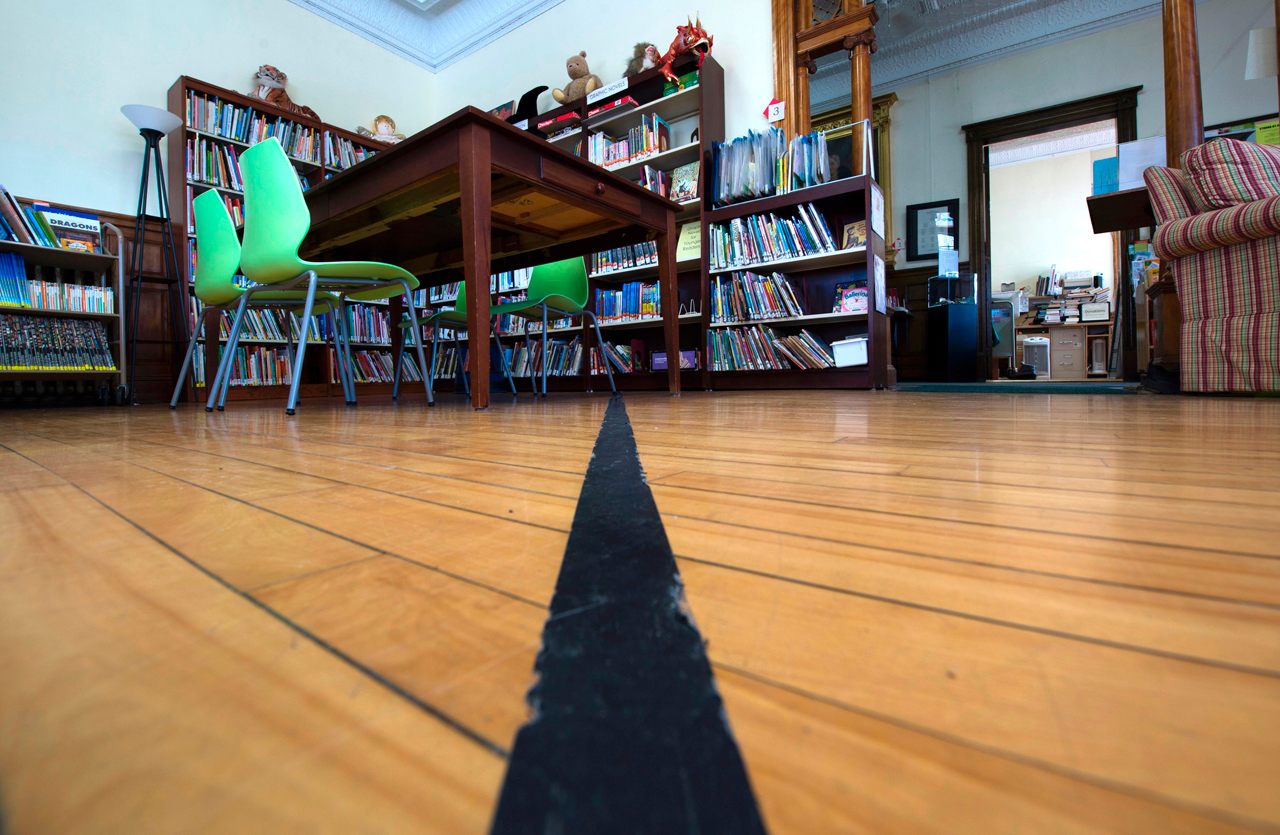

The library downstairs is a bit less ornate–there aren’t any cherubs–but there are carved wooden fireplaces, large bay windows topped with stained glass, and built-in oak cabinets. The elegant fireplace is currently being used to display picture books. A line of electrical tape on the floor demarcates the exact international border. The line itself is a relatively recent addition. After a small fire in the 1970s incited a fight between American and Canadian insurance companies, the parties insisted on bringing in a surveyor to mark the exact border so that they knew who would have to pay out next time.

The librarians try to keep politics out of the cultural center as much as possible, but even they can’t escape the reality of residing on the border. Over the past several years, national security measures have blocked off the unguarded streets which ran between the U.S. and Canada, and created a new series of checkpoints and regulations. The area around the grand old library has become increasingly surveilled by both Homeland Security and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, with nearby streets lined with cameras. There’s always a border guard planted right out front, sitting in an SUV.

It’s easy for Americans to go into the Haskell–they merely walk through the front door. But for Canadians it’s a little more complicated, because they technically have to cross the international line, which is demarcated by a cement obelisk and a line of flower pots. “It does feel a little bit like you’re passing through some DMZ,” library director Nancy Rumery remarks, referring to a demilitarized zone.

While Canadians are guaranteed safe passage to the library, it’s a bit of a harrowing journey. To enter they have to walk past a series of security cameras on Church Street and then past the U.S. border guard stationed out front. As long as they collect their books and walk back the way they came, everything is fine. But if they walk out and continue into the U.S. they’ll be picked up for illegal entry. “We pretend that no one left Canada,” Rumery explains.

But others are less willing to pretend. The symbolic power of the building attracts tourists, but every time the Haskell Free Library and Opera House makes national news (especially after President Obama mentioned the library during Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s visit this spring), Rumery notices an uptick in asylum seekers hoping to take advantage of the unusual nature of the Haskell to cross the border without going through official channels.

The library also regularly sees informal reunions of families divided by immigration restrictions. “Usually it’s an immigrant family where some have settled in the U.S. and some have settled in Canada, and for whatever reason they can’t cross the border and they meet and they’re here for an entire day and they have a picnic on the lawn,” Rumery explains.

Although some people have suggested bringing a border guard into the library, Rumery is holding strong against the idea. Matthew Farfan, President of the Board of Trustees, agrees. “This is a friendly institution,” he insists emphatically. “We’re not in the policing business.”

They convey the sentiment of many residents of both towns who are tired of the increasingly invasive security measures. The Haskell played a small but important role in 2010 during a period of conflict between locals and Homeland Security officials after a new federal grant program, Operation Stonegarden, brought in dozens of out-of-town police officers to help watch the border. Everything came to a head when a local Vermonter named Buzzy Roy was arrested after walking over to Quebec to get a pizza, and refusing to stop by one of the new checkpoints.

Over a few tense weeks outraged residents from both communities held a Free Buzzy rally outside the library, gathered in the Opera House to voice their collective distress with the current policy, and met with government officials, including Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders. Subsequently the local border patrol chief scaled back the police presence in town, but insisted on officially closing off the Church Street entrance to pedestrians, with the exception of library traffic. Residents, however, drew the line at any type of official security border, creating a line of flower pots instead.

Derby Line historian Scott Wheeler has his doubts that this aesthetic border line will hold. “Someday there is going to be some federal official who is going to put a stop to it … I just can’t believe it won’t happen.” But for now this jury-rigged exception to international law holds firm, and Americans and Canadians can enjoy Martha Haskell’s elegant building without a passport.

*Correction: An earlier version of this article mixed up which side of the border the stage is located on. It is on the Canadian side, while most of the seating is located in the U.S.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook