Editor's Note: This story originally appeared in the February 2016 issue of Popular Mechanics to mark the 30th anniversary of the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster on January 28, 1986, when all seven people on board the shuttle were killed. Today marks the 36th anniversary. To hear the voices of the people interviewed for the story, check out this episode of Popular Mechanics' How Your World Works podcast.

For more voices from back then, check out "How to Get America Back Into Space" from the March 1987 issue, published shorty after the Challenger accident.

January 28, 1986, 11:39 a.m., Cape Canaveral, Florida.

It was supposed to be one of the greatest achievements in the history of the United States space program.

A civilian—a schoolteacher, an emissary of the hope for tomorrow—was going to space. Christa McAuliffe, a thirty-seven-year-old mother of two from Concord, New Hampshire, had been selected from eleven thousand entrants to NASA's Teacher in Space contest. She became a symbol of optimism and progress amid Cold War tension. And the rest of the shuttle crew was itself a representation of the strength of American society: Gregory Jarvis, Ronald McNair, Ellison Onizuka, Judith Resnik, Michael Smith, and Commander Dick Scobee. Two women, one of them Jewish. An African- American. An Asian-American. They were the most diverse group of astronauts NASA ever assembled.

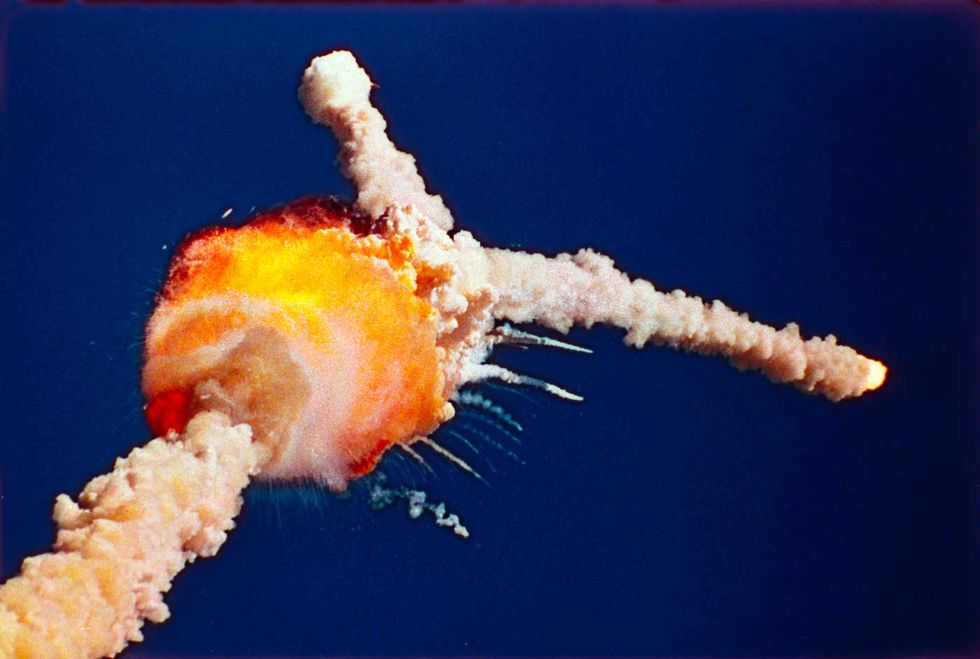

On the morning of January 28, 1986, despite concerns within NASA and among others working on the launch that the weather was too cold, the shuttle Challenger blasted off. Seventy-three seconds later, it broke apart in long, grotesque fingers of white smoke in the sky above Cape Canaveral, Florida.

The shuttle program was retired in 2011. But the sacrifice of the seven astronauts who perished that day should never be forgotten. To mark the thirtieth anniversary of the tragedy, Popular Mechanics found and interviewed more than two dozen people who were closely involved in the launch and its aftermath. Our interviews uncovered new details about not only the catastrophe but also the investigation that followed. Many of these people have never met, but they are linked by that day—bound by horror and loss as well as by endurance and hope. Never before have so many voices of this unfortunate fellowship been collected in one place. Their memories accumulate to tell the remarkable story of one terrible day, its painful aftermath, and its hopeful legacy.

I. "Nice and clear"

Originally scheduled for January 22, the launch of Challenger was delayed or scrubbed five times in six days due to weather and mechanical issues. Another attempt was scheduled for Tuesday morning, January 28. The night before, the temperature dropped into the 20s.

Steve Nesbitt (NASA public affairs officer working at Mission Control): There had been a couple of scrubs in the days before. That was not unusual. Some of the most conservative people you will ever find are in Mission Control. If something wasn't right, they were quite willing to delay and come back another day. But that mission just went on and on. A friend of mine had been scheduled to do it, but he was so tired. So I said, "Let me take your shift for you. I'll do the launch of Challenger."

Bob Hohler (journalist for Christa McAuliffe's hometown newspaper, The Concord Monitor): I remember Christa's parents being frustrated and they told me she was getting frustrated too. It's hard just to keep going through the launch-day preparations. That's a big production.

Johnny Corlew (member of the closeout crew, which secured the astronauts in the spacecraft and sealed the hatch): I was on every one of the attempts. I didn't get tired of it. It was an honor to be able to work with the astronauts.

Carl McNair (brother of Ronald McNair): Monday night Ron called me and said that because of the icy conditions it didn't look like they were going to launch. My wife was pregnant with our daughter, and she really didn't need to be hanging around for an indefinite period of time. So we came back to Atlanta. My mother and aunt and Ron's wife stayed down there. I regret that to this day.

John Zarrella (CNN correspondent): On Monday night a cold front was coming into Florida, so the network decided to send me out into the orange fields to cover the freeze. We were out there all night, then ran back over to the Kennedy Space Center. We thought we'd cover the launch, go back to the hotel, go to sleep, then head back home. That morning was bitter cold.

Hohler: I remember driving in to the Space Center on this sort of eerie dark morning, this sort of pearly sky. I'd never seen a launch before, so I didn't understand as well as I do in hindsight how cold it was.

Nesbitt: I do remember feeling unsure whether we would be going on that particular day because it was quite cold. I remember seeing the video from the Kennedy Space Center of ice teams looking at icicles hanging off the spacecraft.

John Tribe (chief engineer for Boeing/Rockwell Launch Support Services): I described it as the icehouse scene from Dr. Zhivago. I said, "There's no way we're going to fly."

Corlew: When we brought the astronauts out there, we reminded them to use the potty on the Astrovan because the one at the 195-foot level was frozen. I told [Commander] Dick Scobee, "It's pretty cold to be flying today." And he said, "No, it's great weather to be flying in. Nice and clear."

Zarrella: There wasn't a cloud in the sky. You could cut that sky with a knife. It almost looked like the sky was frozen. At eleven o'clock, everybody went down from the press mound over this grassy field, out to where the countdown clock was.

Challenger was the second of fifteen planned shuttle launches in 1986—six more than the year before. Launches had become so routine that none of the three network television stations broadcast Challenger live—only CNN and a few local stations. However, NASA set up a special feed to McAuliffe's school and hundreds more around the country so kids could watch from their classrooms.

Megan Raymond (Concord High School student): I remember realizing the whole country was going to be watching this launch, and that we were going to be at the epicenter of that. I was sitting in the cafeteria, and there were tons of media—zoom lenses right in your face, microphones right in your face. They wanted to get a moment-to-moment reaction.

Kent Shocknek (anchor for Los Angeles NBC affiliate KNBC): Our station had committed to covering the launches and landings when other stations weren't. We went in that morning with a very small crew. We didn't use our main news set—that would have been too expensive just for a five-minute broadcast. We used this tiny, shoebox studio with a locked-down camera, no cameraman. We used the NASA feed and I would just narrate over it. I had a big three-ring reference binder on the shuttle program that I would take into the studio with each launch. So I went in with my binder and a glass of water and I got ready to do what I always did—to interpret what was going on.

Dan Rather (CBS Evening News anchor): I was seated in what we call the fishbowl, the small glass room where we made decisions about what was going on the evening news. I'd been covering NASA since the early 1960s. Back when there was a plan to put journalists into space. I had dreamed of being that journalist. I'd have gone in a second.

Rhea Seddon (astronaut): I happened to be at an off-site building [near Johnson Space Center in Houston], doing some training for my next mission. The launch was supposed to start around the same time as our meeting, so we found a TV and turned it on. It's always a joyful morning, especially to see friends go to space.

Corlew: We made sure they were all properly suited before they went into the shuttle, made sure everything was right, made sure the hatch was closed properly. The whole crew was really jovial that morning. It was a joke between me and Christa: I'd told her I was going to bring her an apple. The day before she said, "Where's my apple?" So the day we launched, I made sure she got her apple. She handed it back and said, "Save it for me. I'll eat it when I get back."

Barbara Morgan (Christa McAuliffe's alternate; trained with the Challenger crew): The crew was fantastic about integrating Christa really well. Dick Scobee did a great job of helping us understand the risks. There are many ways for things to go wrong. He told us that they would more likely be people issues than equipment issues.

Tribe: I couldn't believe they came out of the MMT [Mission Management Team] meeting with a recommendation to launch. Based on the ice alone, I thought it would be no-go. The ice was an unknown.

II. "Go at throttle up"

June Scobee Rodgers (wife of Dick Scobee): The families watched the launches from on top of the Launch Control Center. We had been watching the television in a room inside the building during the countdown, and we went up on top for the actual launch.

Susan Capano (Concord High School teacher): I was in a classroom that seated thirty kids, and there were maybe sixty kids in there and another eight or ten teachers. The school was just overwhelmed with excitement.

Randy Kehrli (staff counsel for the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident, also called the Rogers Commission): Watching a launch [in person], your heart goes up into your throat. The ground shakes under your feet. It's just the most impressive physical experience, most impressive performance of a machine I've ever seen. And it's like, my gosh. We can do this?

Zarrella: Astronauts have told me over the years that the space shuttle is clearly the most complicated vehicle ever built. There's no doubt about that. Fly off like a rocket, go into space, service the Hubble Space Telescope, grab onto satellites, fix them in the cargo bay, throw them back into orbit, build an International Space Station. And then when the job is done, land back on Earth on a runway. We're never going to see that again in our lifetimes.

McNair: After Ron made his first trip to space [in 1984], he came over to my house with this video of it, and he said, "Let's check this out." We connected it to my speakers—I had these big four-foot speakers. Those things were just woofing. He just wanted to watch the actual launch part over and over again, the first minute, just the roar of the space shuttle. It finally blew out my speakers.

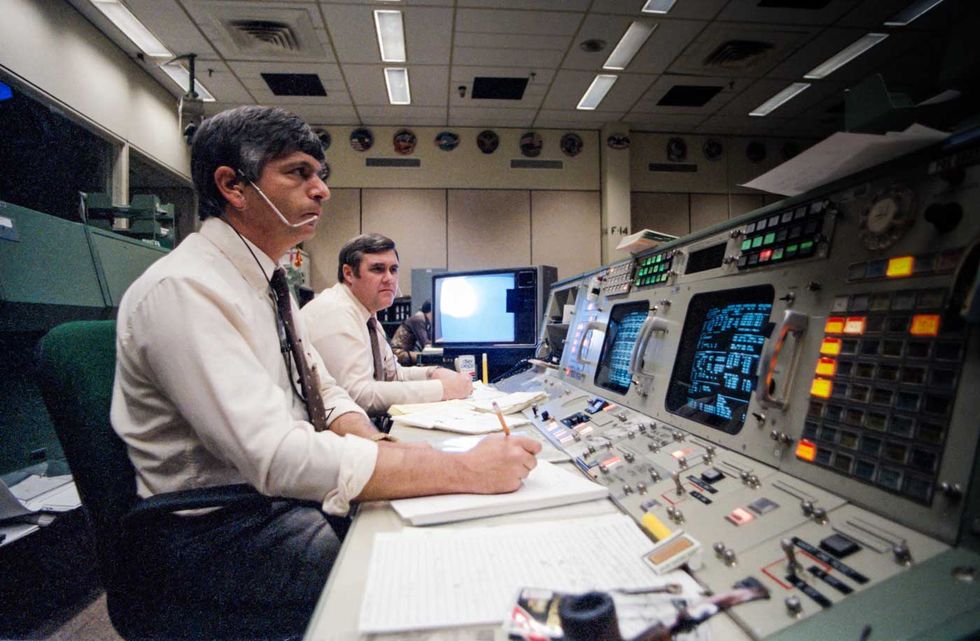

Nesbitt: I had two screens in front of me that I could use to call up a variety of data, like the engine performance, velocity, altitude, downrange—all the flight parameters. And there was a color television set farther off to the left. I typically did not watch that, because once the launch occurred I was just going crazy trying to gather all the data, jumping back and forth between places on the data screens so I could pick information up.

Dick Covey (astronaut who, as capsule communicator, or capcom, for Challenger, was the sole voice of communication to the crew from Mission Control): We had been disciplined to watch our data, not to get distracted by watching whatever video might be running in the control center. So I'm watching my data, and there's nothing unusual through the throttle up. The engine guys confirm that the engines look good, so I make a call: "Go at throttle up." Dick [Scobee] responded. And then I'm starting to think about what's the next thing that's coming, if we're going to make a call or whatever, and the data just went all M's, which is "missing."

Nesbitt: I heard the capcom say, "Go at throttle up," and then Dick Scobee came back and said, "Roger, go at throttle up." And right then you hear the crackling in the audio. I heard the crackling—but we were always losing communication and picking it up again.

III. "Everybody shut up. Something's wrong."

Brian Perry (NASA flight dynamics officer): The first indication that we got of any kind of trouble was when I got a call from one of our backroom folks who's in charge of processing the radar coming in. We have at least three different radars tracking the vehicle at any time, and they all have to provide a consistent indicator of where the shuttle is. She reported that the filter [the software] had disagreeing sources, which is not normal but not necessarily unheard of. You can get birds and airplanes and stuff in the way. So that by itself didn't necessarily concern me.

Covey: Fred [astronaut Fred Gregory] was in charge of weather and so he was able to watch the video, and he almost immediately says, "Look!" And so I turned and I looked, but I didn't know what I was looking at. I didn't see how it originated, nor did I understand exactly what it was. It just didn't register with me.

Nesbitt: Sitting to my left was a Navy flight surgeon. She was able to watch the TV screens, and as I was speaking I heard her say, "What was that?" I paused for a minute and looked over, and I saw the two SRBs [solid rocket boosters] veering off on wild separate rides.

Seddon: I said, "Oh, look, you can see the boosters are coming off." And one of my crewmates said—he was looking at his watch—"No, it's too early." We weren't supposed to jettison the boosters until they were burned out.

Shocknek: My first thought was that perhaps an SRB had fallen off prematurely, but the size of the explosion and the asymmetry of that fireball—I knew this was not a solid rocket booster being jettisoned. I remember saying, "My God"—not something I would say in the course of any other broadcast day.

Zarrella: From our vantage point, we could not see the fireball from the ground. We couldn't see it. I remember distinctly you could see the cloud of smoke and it appeared there were fireworks that were shooting out from behind the cloud. We stood there for what seemed like an eternity. We were all looking at it, watching. And looking at each other, because we all knew something was wrong.

Capano: The kids in the classroom were shouting and cheering as it launched. And then we started hearing things from the TV. The kids were talking, they were all excited, and we had to quiet them because we'd started hearing that something had gone wrong.

Raymond: I remember seeing the explosion, the two streams of white smoke, and realizing there was no shuttle in the middle. I remember thinking specifically: Wait, that doesn't look right. I remember hearing cameras clicking. I remember one of our beloved teachers standing up on the cafeteria table and shouting, "Everybody shut up. Shut the hell up. Something's wrong." We respected him so much that when he did that, we got really scared, because he was scared.

Seddon: The camera panned back, and all you could see was a cloud of … stuff. We thought the engines were still going with the shuttle attached to the tank. Then they showed the ocean, and there were pieces coming down—big chunks of something.

Tribe: In the firing room [in Launch Control at the Kennedy Space Center], we could see it out the window. All I remember now is one wing spiraling down, like a leaf coming off a tree. Of course it was plummeting down, but it looked like it was slow in real life. We were stunned.

Hohler: I was taking pictures of Christa's parents, with my back to the launch. So I didn't see it myself. I just watched her parents' faces as it occurred. And I knew right then that life was never going to be the same.

IV. "There was a period of something like disbelief"

Scobee Rodgers: I couldn't hear what was being said. It wasn't clear what had happened. We came down from the roof, and we were gathered around the television. Then I was seeing replays and I heard the words "major malfunction."

Nesbitt: I kind of paused to gather my thoughts, hoping to hear something on the flight director loop. There was nothing for several seconds, and I felt an urgent need to say something, to plant a flag here that acknowledges something terrible or unusual has happened. But I didn't actually know what was going on. I didn't want to say, "The spacecraft has exploded," because I didn't know that for sure. I wanted to be correct. So I said, "Flight controllers looking very carefully at the situation. Obviously a major malfunction." Some people criticized my delivery, criticized that as being an understatement when clearly the crew had just died. But in those immediate seconds right afterward, that information was not available, and my own sense of professionalism would not let me make that kind of statement, that the crew was lost, without having that confirmed.

Perry: After a while [the inconsistent data] went on longer than we thought reasonable, especially when we weren't getting any calls from onboard. So I asked my traj [trajectory] guy, who's talking to the range-safety people, to ask if they were seeing anything. The guy down at the range responds, "It all blew up." Traj and I look at each other, and traj says, "Say that again?" And he says, "It all blew up!" And traj says, "What did?" And he said, "The shuttle." And that was when I made the call to [flight director] Jay [Greene]: "RSO [range safety officer] reports the vehicle has exploded." That was the first that a lot of people in the room knew about it.

Capano: We got the kids quiet, and then I remember that the line that came across the TV was "The vehicle has exploded." One of the girls in my classroom said, "Ms. Olson [Capano's maiden name], what do they mean by 'the vehicle'?" And I looked at her and I said, "I think they mean the shuttle." And she got very upset with me. She said, "No! No! No! They don't mean the shuttle! They don't mean the shuttle!"

Raymond: The principal came over the PA system and said something like, "We respectfully request that the media leave the building now. Now." Some of the press left, but some of them took off into the school. They started running into the halls to get pictures, to get sound—people were crying, people were running. It was chaos. Some students started chasing after journalists to physically get them out of the school.

Rather: I remember seeing it on the monitor. There was a period of something like disbelief. There wasn't any question I had seen what I'd just seen, but it was such a shock. I remember the plume of smoke. It was eerie—the plume of smoke formed a fork, like a wishbone. I remember saying some version of, "God almighty, this thing has just blown up." I ran to the studio, went live on the air. The maximum test of anchoring is major network television coverage of a disaster. Because you're operating without a script. In one ear, I had the director of the program giving me directions—for example, "Go to this correspondent." In the other, I had researchers giving me a constant flow of suggestions, checking and double-checking facts. It's a constant ad-lib situation. From the moment it happened, I knew we'd be on the air until late at night, and indeed we were.

Jean Becker (USA Today reporter): I was in the newsroom that day, in Washington, D.C. I can see myself sitting at this big round desk. About half of the newsroom was watching it. There was just this eerie silence, and then a sense that we had to get to work covering this. I can still see the main editor coming out of her office and barking, "Jean! You're on your way to the airport right now. Get your purse, you're gone." I didn't go home. I didn't pack. I didn't even have a toothbrush. I just got on the plane and went down there.

Zarrella: I was running up to the press dome to find out from the NASA public affairs people what was going on. My cameraman was on an elevated mound, and as I ran up, he had his head up to the eyepiece and his camera trained on the cloud. And I'll never forget: I said, "Steve, what happened?" And he looked away from his eyepiece and he said, "The f—ing thing blew up." Those were his exact words. I headed right up into the press dome, and when I got there it was already bedlam.

Jake Garn (U.S. senator and crew member on a 1985 shuttle mission): I was watching from the main visitors' area. I had flown myself just six months before. I knew this crew personally. We didn't train for the same flight, but we were in training at the same time. Just after the explosion, it was just hugs and tears. Just sort of disbelief. Is this really happening? The mind doesn't function too well when you go through a tragedy like that.

V. "Mr. President, the Challenger exploded"

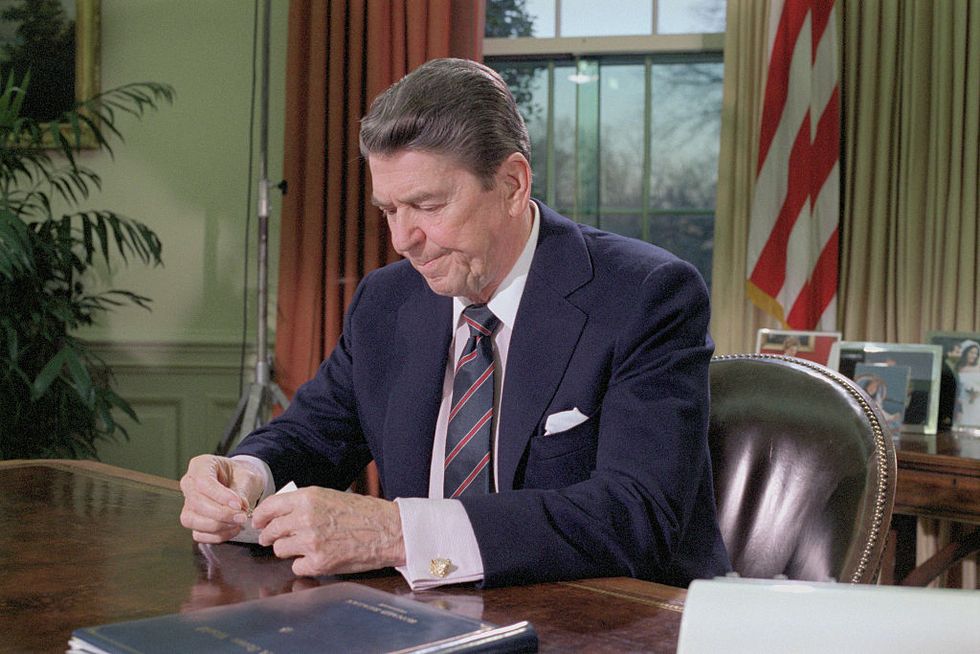

Kathy Osborne (executive assistant to President Reagan): I received a phone call from White House staff people who saw it on TV in another room. The president was in the Oval Office with his White House senior staff. They were having a meeting about the State of the Union speech, which he was supposed to deliver that night.

There were two ways to come in to the Oval Office. People could come through the Roosevelt Room, which is a prettier way to enter, so we brought outsiders through that way. Or they could come through my office, which is what staff always did. Nobody walked into the Oval Office unless they saw [executive assistant] James Kuhn and myself first, because they didn't know what was going on in the office and we did. When I got that phone call, I hung up and, rather than just going right into the Oval, I felt like I needed to turn on the TV. I was horrified by what I was seeing replayed over and over on the screen. After a couple of minutes, I went into the Oval Office and the president was in the process of talking. I was standing there with the door open, holding it open and just waiting a few seconds for him to finish his sentence. [Press secretary] Larry Speakes was on a couch facing me, and he could see by the look on my face that something was wrong, and he stood up. And just as I started to say, "Mr. President," Pat Buchanan almost knocked me over trying to get through the door to the Oval Office and shouted something like, "The Challenger exploded."

James Kuhn (executive assistant to President Reagan): Pat Buchanan came tearing down into [Kathy Osborne's and my] little reception area and said, "The space shuttle just blew up." He went right into the Oval Office and told the president. We were all so stunned. It was just complete silence.

Pat Buchanan (White House communications director): Reagan looked at me with this look on his face, and said, "Isn't that the one with the teacher on it?" And I said, "Yes, sir."

Osborne: The president's immediate reaction was, of course, a look of anguish. We moved him and most of the senior staff into the president's backup office where the television was. They were back there quite a while, just watching it replay constantly.

VI. "Magical thinking—the hope that they could have survived"

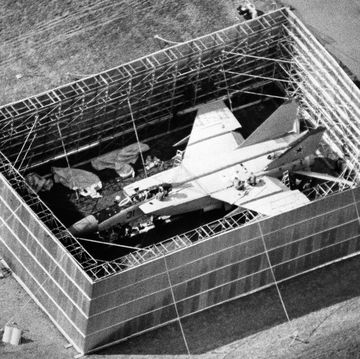

Live TV images offered a glimmer of optimism: the sight of a parachute descending. But it was only the shuttle nose cap. At first, the prevailing story was that the crew had been killed instantly. However, later investigations revealed that the cabin had been severed from the shuttle and projected free of the fireball, and that the crew had briefly survived. Despite plummeting at more than two hundred miles per hour, the cabin would take almost three minutes to reach the ocean. Only after six weeks of searching were their bodies recovered.

Pat Smith (brother of Michael Smith): I was down in Florida for some of the launch attempts. I left and headed home to North Carolina. I was still on the road, coming home with my wife and children, just ten minutes from home, and I said, "It's time for the launch. Let's see if we can find anything on the radio." We didn't have to turn the dial very far to find out what had happened. Everybody was talking about it. My wife asked, "Do you think they got out?" I said, "There's no way they got out."

Hohler: I had this sort of magical thinking—the hope that they could have survived.

Covey: At best, the orbiter was separated from everything else and maybe trying to find a way to fly. And the worst thing in an emergency when you are flying is to have someone on the ground trying to talk to you without giving you the help that you need. So I was reluctant to be a distraction unless I had something I could tell them. If they weren't talking to us, then they either didn't have the ability to talk to us, or they were busy enough that they didn't want to talk to us. I asked for emergency procedures, contingency aborts, anything that we could do to help them. And then it became obvious that there wasn't anything we could do, and we were spectators in a tragedy.

Scobee Rodgers: I knew they had been trained to return to Earth some way, that there were different places they could return to. But when we were standing by the elevator to go up to the crew quarters, the radio was on and we heard, "Everyone lost. No crew members survived. All are lost." I heard that.

McNair: We'd traveled all night getting back to Atlanta, and when I got up I turned on the TV. I saw the shuttle launch, and when I saw that awkward veering of the solid rocket boosters I immediately knew something was wrong. I knew then and there we had lost Ron and all the other astronauts. My wife saw me just shattered, weeping, and she said, "What happened?" When my dad finally got up, I told him, "Dad, you have to see this." Not until that day, and never after that day, had I seen my dad cry. I can feel it now, that feeling.

Raymond: I just remember walking the hallways and seeing faculty members sitting by themselves in an empty classroom at a desk, just in total shock. I remember a student who had been really close to Christa, and he was just pounding a locker door over and over again with his fist.

Shocknek: My obligation was to be as composed as possible for viewers, but I was shaken up. It's pretty obvious if you look at the video after we lost our signal and the director punched up the camera on me in the studio that I had to take a big swallow and try to come up with airworthy information. With everything that was going through my mind, the one thing that didn't—until I was off the air and slumped back in my chair—was the realization that I knew two of the astronauts. Over the years I had a couple times run into El Onizuka and Judy Resnik. I remember how friendly they both were. To not even realize until later that I knew two of those folks struck me as a reminder of what an amazing thing the mind is—pushing things forward that are needed right at the moment and burying away those that are not.

Scobee Rodgers: We were standing there in the crew quarters in a circle, the families, when Vice President Bush, Senator John Glenn, and Senator Jake Garn came to us, these people grieving. I looked at everybody, waiting for someone to say something. No one spoke up. So I thanked them for coming. And I said that our loved ones valued their mission and the value and importance of spaceflight. And that to a person, I think we all would agree, spaceflight should continue.

George H.W. Bush (vice president): While I was meeting with the families, June Scobee Rodgers looked me in the eye and begged me not to let what had happened to her husband and the Challenger end space exploration.

Garn: I had some feeling for what the families were going through because I lost my first wife in an automobile accident. It's difficult when a friend dies, but to lose a whole group at once …

VII. "He knew he was speaking to the children of America"

Buchanan: We called in Peggy Noonan, told her what we needed was a short speech for the president to talk about what had happened. She must have written it in an hour and a half.

Peggy Noonan (speechwriter and special assistant for President Reagan): If you worked for Ronald Reagan, you knew what Ronald Reagan thought. He knew he was speaking to the children of America, but he also knew at the same time he was speaking to the adults of America. And he was speaking to the world at a time of Cold War tension. He knew those opposed to us would see this as a military setback. So he had to speak to everybody, and not patronize anybody. And of course, because he was Reagan, he could.

The State of the Union was postponed, and President Reagan delivered a nationally televised address from the Oval Office at 5:00 p.m. Just four minutes long, it is considered one of the greatest speeches by a sitting American president and included the invocation of a sonnet by early twentieth-century British-American poet and aviator John Gillespie Magee, Jr. "We will never forget them," Reagan said, "nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and slipped the surly bonds of Earth to touch the face of God."

Kuhn: I was right there in the Oval Office with him while he was giving that address. Reagan was a tower of strength that day and going forward. He was always steady in the worst of times and steady in the best of times.

Noonan: It didn't seem that the president was satisfied with the speech. He seemed even sadder when it was over than he was before. I think we all went home feeling maybe that didn't work. But he called me the next day. He told me that he hadn't thought that it worked, but now he did.

Osborne: The president was asking the staff for more details, like how could this happen, where were the astronauts' families, what could he do to help them. The president said he wanted to call the individual families, but he wanted to wait until the following day rather than imposing on their grief and their privacy that same day.

Kuhn: Part of my job was to make a decision about what calls to put through to the president. I got a call from the president's operator late that night, and she said, "I have Christa McAuliffe's father-in-law on the line, and he wants to speak to the president." And I thought, Oh, boy. This is going to be difficult. I was on the phone with him for about forty-five minutes. His anguish was unbelievable. He said it was President Reagan's fault that Challenger had exploded, and he wanted to know what President Reagan was going to do to make it right. I let him do 90 percent of the talking, and I tried to tell him as much as I could about how anguished the president was. At the end, I told him, "You will hear back from us." I put him in touch with the crisis communications center at the Kennedy Space Center. I talked to a person I knew down there, and she said, "Jim, this is our job. Let us handle it from here."

VIII. "This isn't going to be another Warren Commission"

Less than a week later, on February 3, President Reagan ordered a special investigation of the accident. Headed by former secretary of state William Rogers, the Rogers Commission included Neil Armstrong, Sally Ride, Chuck Yeager, Nobel Prize– winning physicist Richard Feynman, and other experts in aeronautics, aviation, and disaster analysis. Their final report would be a stinging rebuke of NASA and would lead to a two-and-a-half-year suspension of the shuttle program.

Covey: People said, "Well, the external tank obviously exploded," because that was what made the big fireball. But what caused it, nobody had a clue. It was days if not a week before any of us could say, "All right, now I'm starting to understand what went wrong."

Tribe: I was working for North American Aviation at the time of the Apollo 1 fire [in 1967, which killed three astronauts]. We built the Apollo capsule. I was on station that night, and the last test we performed before the fire was Gus Grissom and me working through a static fire simulation. The comm system was bad, and we took a ten-minute break to try to clear it up. It was during that ten-minute hold that the fire broke out. There are a lot of differences and a lot of years between these two disasters, but some of the drivers are the same. The Apollo fire was driven by trying to go too fast. The hardware and the procedures weren't ready. And of course, Challenger was also pushing too hard to meet schedule pressure: launch fever. In our business, it's when you don't do things in a carefully conducted manner that you start to get into trouble.

Donald Kutyna (Air Force general and Rogers Commission member): Bill Rogers was the smartest guy in Washington on how to handle politicians. His main function was to keep the damn politicians—all of whom wanted to get their names in the paper by doing something about the Challenger accident—at bay.

Kehrli: The first thing Rogers said to everybody was "This isn't going to be another Warren Commission. We want to find the answer, the true answer, and we need to do it the right way." We were extremely sensitive to the fact that we would be accused of whitewashing, trying to get NASA off the hook. And we were sensitive to the charge that there was pressure by the White House—we investigated the possibility of White House pressure as a possible cause. I think that was the genius of Rogers and the people who came up with the commission members. There was a wide variety. It wasn't all military. It wasn't all NASA. This was a very hardworking commission. Rogers was there every day. Sally Ride was there every day. Neil Armstrong was there every day. You have to remember at the time how the nation felt about it. How could NASA let us down? They're heroes! They went to the moon! How could these seven people be dead? It was bringing America to its knees. And so for six months we worked seven days a week, twelve hours a day.

Chuck Yeager (Air Force general and test pilot): Finally they were getting some military Air Force guys on it. I was surprised to be included. I had to think about whether or not to participate. I knew that NASA was screwing up.

Alton Keel (engineer; executive director of the Rogers Commission): It took almost every waking moment. I took off only half a day in the entire six months. At first, the commission was serving as oversight of NASA investigating itself. The first hearing was a closed-door hearing, just commission members and the witnesses, who were from NASA and Morton Thiokol [the contractor that had built the solid rocket boosters]. The intent of the meeting was for NASA to tell us typically what happens during launch—not specifically this launch but generally how it was supposed to go. Finally, Allan McDonald from Morton Thiokol, who was project manager for the solid rocket motor, said, "Mr. Chairman, may I say something?" He was quivering in his chair. Rogers said, "Of course." McDonald said, "We recommended not to launch." And then you could have heard a pin drop in the room. Everybody went quiet. Then everything started to unfold from that point.

Kutyna: On STS-51C, which flew a year before, it was 53 degrees [at launch, then the coldest temperature recorded during a shuttle launch] and they completely burned through the first O-ring and charred the second one. One day [early in the investigation] Sally Ride and I were walking together. She was on my right side and was looking straight ahead. She opened up her notebook and with her left hand, still looking straight ahead, gave me a piece of paper. Didn't say a single word. I look at the piece of paper. It's a NASA document. It's got two columns on it. The first column is temperature, the second column is resiliency of O-rings as a function of temperature. It shows that they get stiff when it gets cold. Sally and I were really good buddies. She figured she could trust me to give me that piece of paper and not implicate her or the people at NASA who gave it to her, because they could all get fired.

Kehrli: The engineers from Morton Thiokol had raised holy hell the night before the launch. And they were right. This concern about the joint sealing was not new. They had been working this problem for years, and they hadn't fixed it yet. Engineers were saying, "You can't fly in these conditions." But then NASA kept waiving the launch constraint from flight to flight. It's like Richard Feynman said, "That's like playing Russian roulette. Sooner or later it was going to get you." And that's exactly what happened.

Kutyna: I wondered how I could introduce this information Sally had given me. So I had Feynman at my house for dinner. I have a 1973 Opel GT, a really cute car. We went out to the garage, and I'm bragging about the car, but he could care less about cars. I had taken the carburetor out. And Feynman said, "What's this?" And I said, "Oh, just a carburetor. I'm cleaning it." Then I said, "Professor, these carburetors have O-rings in them. And when it gets cold, they leak. Do you suppose that has anything to do with our situation?" He did not say a word. We finished the night, and the next Tuesday, at the first public meeting, is when he did his O-ring demonstration.

We were sitting in three rows, and there was a section of the shuttle joint, about an inch across, that showed the tang and clevis [the two parts of the joint meant to be sealed by the O-ring]. We passed this section around from person to person. It hit our row and I gave it to Feynman, expecting him to pass it on. But he put it down. He pulled out pliers and a screwdriver and pulled out the section of O-ring from this joint. He put a C-clamp on it and put it in his glass of ice water. So now I know what he's going to do. It sat there for a while, and now the discussion had moved on from technical stuff into financial things. I saw Feynman's arm going out to press the button on his microphone. I grabbed his arm and said, "Not now." Pretty soon his arm started going out again, and I said, "Not now!" We got to a point where it was starting to get technical again, and I said, "Now." He pushed the button and started the demonstration. He took the C-clamp off and showed the thing does not bounce back when it's cold. And he said the now-famous words, "I believe that has some significance for our problem." That night it was all over television and the next morning in the Washington Post and New York Times. The experiment was fantastic—the American public had short attention spans and they didn't understand technology, but they could understand a simple thing like rubber getting hard.

I never talked with Sally about it later. We both knew what had happened and why it had happened, but we never discussed it. I kept it a secret that she had given me that piece of paper until she died [in 2012].

Keel: We recorded every single document that came in and out, every phone call, every piece of correspondence. No matter how obscure or how fanciful the charge, we investigated it. We got people saying aliens did it—we had an investigator go out and talk to that person. We wanted the report to be a narrative and not just technical information—to tell a story, to have an effect. The only person who hung around while it was being edited who didn't have to be there was Neil [Armstrong]. He would have a nip of single-malt scotch and regale us with stories about landing on the moon with Buzz Aldrin, looking for a place to land while the fuel was running out. If you ask me in hindsight would I do anything differently—at the risk of seeming immodest, the commission got it right.

Kehrli: I do not think it was a cold, intentional calculation on NASA's part. I think it was a flaw in the decision-making structure of NASA. I think there were some incorrect judgments, but they were judgments. It might have been negligence. It probably was negligence. But in terms of criminal, cold, calculated intent, I don't think there was any of that.

Covey: It was disappointing, angering almost, to find out that discussions had been held relative to [the known issue of joint failure in solid rocket boosters]. Why wasn't that a bigger issue? How did we get to the point of accepting that indicator of a system not working the way it was designed? Why had we been willing to accept that?

Rather: The media were enthralled with the space program, including this reporter. We didn't ask enough questions. When it became clear that the morning was going to be cold, an alert and deep-digging media would have figured out that it's more dangerous. That should have been a bigger caution flag. Frankly, in the end I don't think it would have made a difference. The decision-makers at NASA were hell-bent to launch that morning. NASA's argument was that when you go to frontiers that are so dangerous, nobody should be surprised when disasters happen and we just need to accept that as inevitable. I questioned that at the time, and as the years have gone by I still question it.

Smith: What really bothered me is that they knew there was a chance it was going to happen. That is awful. That is unbelievable. When those people knew they were putting those seven people on that space shuttle with a chance of them dying, I have a real problem with that. I have a problem with anybody who plays with other people's lives.

Keel: Part of the mistake we made and that NASA made was starting to think of the shuttle as a cargo plane while it was really still an experimental program. The probability of failure was 1 percent. If you applied that to commercial flight, that's thousands of crashes a day. We began to think of it as too routine.

Yeager: NASA wanted the pub-licity for the launch. The launch had been scrapped several days in a row and the media was leaving. So they ordered the launch. They got their publicity, all right.

Tribe: I haven't forgiven the guys that overrode the O-ring decision.

IX. "Nightmares"

In addition to the suspension of the shuttle program, NASA would undergo a significant overhaul, including sweeping personnel changes and a new management structure, while both the government and contractor Morton Thiokol would pay millions in settlements to the astronauts' families. But none of that would lessen the trauma and grief.

Bush: At age ninety-one, my memory is not what it used to be. I am beginning to think I have now forgotten more than I ever knew to begin with. But like all Americans who are of a certain age, I remember the day the Challenger blew up.

Nesbitt: I ended up being the last person to leave Mission Control that day. My emotional feeling at the time was like a house dropped on me, and I have sort of felt it ever since. For many years I thought of it practically every day. I've often seen the picture of Christa McAuliffe's parents with the look of shock on their faces. And I've wondered if my voice or what I said contributed to their grief. Did I sound too cold in my delivery? Obviously that kind of thing haunts you.

Becker: I finished writing my piece around midnight that night. I was pushing deadline. And I remember going outside and seeing the launchpad just bathed in floodlights. And I remember just sitting down and crying.

Kuhn: A few days later, we went to Houston, to the Johnson Space Center, for the memorial service. There were fifteen thousand people there. The Reagans met with the families privately ahead of time. The president let them talk. There were twenty-five or so family members in there, and he went to each one individually, told them how sorry he was and then he let them talk to him. He listened. The family members were strong that day.

Kathie Scobee Fulgham (Dick Scobee's daughter, who was twenty-two at the time): I'd never even lost a grandparent. I had no idea what death meant. I did not believe it. I was having nightmares about him being stuck on a piece of space shuttle floating around in the ocean.

Rather: This event set a precedent for coverage going forward in which the video was so spectacular, so tragedy-laden, that we repeated it over and over again. It's at the point where now—and I include myself in this criticism—it tends to be overdone.

Raymond: I remember the media wanting to capture this mourning community and students in pain. People just want to see that. It's like having to stop and look at a car wreck. I remember the windows of the first-floor classrooms had to be covered with paper, because a few journalists were standing on each others' shoulders and holding cameras through the windows just to get pictures. But it was really incredible how much the school and the community came together. Students would stop and check on faculty throughout the day. Just pop your head into a classroom and check on a teacher and say, "How are you doing?" All those hierarchies melted away. It lasted a very long time.

Scobee Rodgers: After we were back home we could not turn our TV on without seeing it. We'd go to the grocery store and see the front page of newspapers, magazines—everything was a reminder. I'll never forget the first time I went to the grocery store. In my mind I wasn't a widow yet. I was still Dick Scobee's wife. He loved peanut butter, and I went over and picked up a jar of peanut butter like I always did. And I sat down in the store and cried, because I didn't have anyone to take that peanut butter home to. There's not a day that goes by that I don't think about him.

Scobee Fulgham: When grief is public, I think it's so much worse. Grief is very complicated—there is nothing simple about it. It is not a straight line. Sometimes it's okay, and sometimes, even now, there will be days when I really miss him. Or there's something that the kids have done that I really wanted him to see, and I'll just think, I really wish he was here. He loved Christmas. Christmases always make me miss him.

Seddon: I think there were a few astronauts who left the program because their families worried about them. I think if my kids were really traumatized by it, my decision might have been different. But at the time my kids took it as a regular part of life. Hoot [Seddon] and I were committed to this life and these risks, and we were ready to go forward. We wanted to continue flying.

Corlew: That night I went home, I told my wife, "I don't want to talk to nobody." I went back to work the next day and I told my boss, "Put me on annual leave." I went to Lake Okeechobee and fished for three weeks. I couldn't do it anymore after Challenger. They asked me if I wanted to be on the closeout crew, and I said, "No." I wouldn't even watch a launch until after "Go at throttle up." Only then I would turn and look at it.

X. "We learn from our mistakes and tragedies"

In September 1988, the shuttle program resumed, carrying out eighty-seven missions without incident. That streak ended in 2003, when the shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon reentry, killing all seven crew members. Noting that "the causes of the institutional failure responsible for Challenger have not been fixed," the Columbia Acci dent Investigation Board recommended the shuttle be allowed to fly until the International Space Station was complete, then be either recertified or retired. In 2011, NASA sent up a shuttle for the last time. Yet the Challenger legacy continues to foster interest in space exploration, science, and engineering among new generations.

Nesbitt: It was two and a half years after Challenger when we launched again. I asked my boss if I could do the launch commentary because I felt like I had an incomplete job that I needed to do. For that mission and every one after that, I always had my fingers crossed for that first two minutes and five seconds until the solid rocket boosters separate. Even though there were plenty of other bad things that could happen, once the SRBs separated and the main engines were going, I felt a lot better.

Kehrli: I was there for that return-to-flight launch. NASA flew me down to see it. Yeah, I was scared. I remember going, "Come on, Rick [Commander Rick Hauck]! Come on, Rick, fly this thing! Fly it, fly it!"

Morgan: NASA had scheduled appearances for Christa and me, for after she returned from the flight. We were to share our experiences with people all over the country. After the accident, NASA asked if I would carry on and serve in Christa's shoes as Teacher in Space designee. I thought it was important for kids to see how adults should respond to terrible situations.

Yeager: My last job in the Air Force was as director of safety. When I got there, the policy regarding the approach to investigating accidents was finding a primary cause and secondary causes. I went to General [Michael E.] Ryan, who was chief of staff of the Air Force, and told him: "They are only correcting the primary cause and not the secondary cause." I suggested we change it to "all-cause" accident so that all the causes would be fixed. He agreed, so we did. The airline industry followed suit, which prevented many, many accidents. But NASA didn't do this. Even after Challenger, they did not fix them all. They knew about the issues before the Columbia accident and didn't fix them.

Morgan: The families wanted something that really represented and continued the crew's mission for education. They put together the Challenger Center for Space Science Education, which to this day is still making a huge difference. Many years later, one of my astronaut classmates told me that she was in junior high at the time [of]. She saw Christa and was able to connect with her, and that's when she started seriously thinking about taking the path to become an astronaut. That means so much to me.

Smith: The real legacy of Chal-lenger is a positive one. The Chal-lenger Centers that June Scobee and Jane Smith [wife of Michael Smith] and the other families started, that is a real positive thing. It gets young people interested in space. And the space program has been a huge positive. Was it worth the cost? I'd have to say yes. Although the astronauts lost their lives, I'd have to say yes.

Raymond: I have several good friends from that time who went into education. I'm still in education. Certain things that Christa said will always stay in my head. She had a profound impact on us. She was just such a naturally gifted teacher. She could always see the statue in the stone.

McNair: I think the Challenger Centers and the McNair Scholars Program are the real legacy of Challenger. Ron had been planning to go back to education, to teach physics at the University of South Carolina, the very same school that wouldn't accept him as a student [because it was segregated at the time]. Over sixty thousand students, either economically disadvantaged or first-generation college students, have been McNair Scholars—probably more people than Ron ever would have impacted in his lifetime. Not only those McNair Scholars, but the people they've impacted, the students they've taught.

Bush: I believe that the legacy of the Challenger is the very spirit of the American people. We learn from our mistakes and our tragedies. And then we move on. And we do things bigger and better than before. Challenger is one of our best examples of that. The remarkable June Scobee Rodgers moved on by helping establish the Challenger Centers, which bring the joy of science and space to hundreds of thousands of our children. NASA, and our country, moved on by reaching even deeper into outer space. We have had spacecraft exploring Venus, Mars, Saturn, and Mercury. And today we have an American, Scott Kelly, commanding the International Space Station. By the time he comes home, he will have set a record for the longest time in space by a U.S. astronaut. On the day the shuttle blew up, I said, "Our fallen astronauts have taken their place in the heavens so that America can take its place in the stars." I hope the crew of the Challenger would feel we have honored them well. I think they would.