Why Is American Beer So Bland?

Blame Prohibitionists, German immigrants, and factory workers who just wanted to drink during their lunch break.

Today’s discerning beer drinkers might be convinced that America’s watery, bland lagers are a recent corporate invention. But the existence of American beers that are, as one industry executive once put it, “less challenging,” has a much longer history. In fact, Thomas Jefferson, himself an accomplished homebrewer, complained that some of his country’s beers were “meagre and often vapid” nearly 200 years ago.

Jefferson never lived to see the worst of it. Starting in about the mid-1800s, American beer has been defined by its dullness. Why? The answer lies in a combination of religious objections to alcohol, hordes of German immigrants, and a bunch of miners who just wanted to drink during their lunch break, says Ranjit Dighe, a professor of economics at the State University of New York at Oswego.

Dighe’s history of the industry, which was published in the journal Business History earlier this year, starts with British colonists in America who preferred dark beers, reminiscent of today’s porters and stouts and similarly alcoholic, containing about 6 percent alcohol by volume. But since those beers required imported malted barley, they were expensive, and early Americans made the first fateful move toward boring beer: They started brewing with corn, wheat, and molasses instead.*

But Americans didn’t develop a more unified taste in beer until the mid-1800s, when huge numbers of German immigrants—including David G. Yuengling, whose brewery still operates today, outside of Philadelphia—arrived and brought lager with them. Less intense in flavor than porters, stouts, and ales, lagers were a hit with America’s growing number of factory workers and miners, who ate at saloons near where they worked. “It was normal to get a beer with your meal, but not allowable to be tipsy on the job,” says Dighe. “So if you wanted a beer, your safest option was a weak beer.” As more and more immigrants came to the U.S. and unemployment stayed high, the stiff competition for jobs made this pressure for sobriety even higher.

From this perspective, wateriness was not a bug, but feature. In the late 1800s, when Anheuser-Busch started selling a milder version of Budweiser made with rice, it cost a nickel more than its competitors—and it sold quite well.

At the time, beer labels didn’t include information about alcohol content, so flavor and color were usually the way these workers evaluated beer’s strength. “The milder the taste, the milder the beer, would be a natural assumption,” says Dighe. Lagers were golden-brown in color, leaving room for an even lighter beer to quench American workers. That came in the form of an especially pale lager from the Bohemian city of Pilsen—called a pilsner—that had become popular across Europe. It did the same in the U.S., where beer consumption per capita tripled between 1875 and 1915.

Meanwhile, as miners and factory workers were finding professionally acceptable ways to drink during lunch, the Temperance movement was gaining support. Initially many in the movement, which started in the 1820s, only set out to curb the consumption of liquor, figuring that a ban of all alcohol might repel potential adherents. Brewers, aware that they could be next, trumpeted their products as temperate alternatives to liquor. But as the Temperance movement found success—spirits consumption per adult dropped 80 percent between 1830 and 1900—they pushed for beer bans as well.

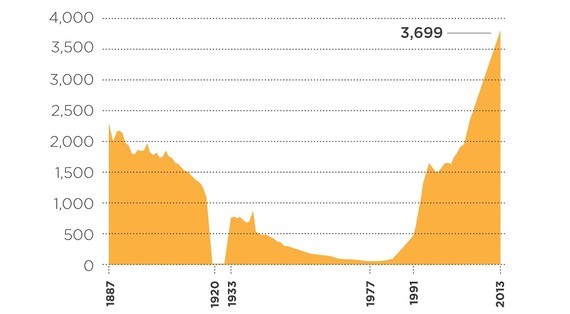

In the short term, the Temperance movement triumphed. Prohibition went into effect in 1920 and put 1,568 breweries out of business. In response, some families started brewing their own beer, but most didn’t, and a decade-and-a-half without full-bodied beer, Dighe and other historians have suggested, made Americans lose their taste for it.

By the time Prohibition was repealed, the breweries that opened went with what they knew would sell in the 1910s: light, bland beers. One man who witnessed a batch of particularly strong beer go unsold at the time said, “It is just too much hop for this generation.” And even if Prohibition was over, the Temperance movement’s efforts to ban alcohol at the state and local levels wasn’t: The beer industry’s reluctance to offend it permeated the pages of trade publications for decades; cowed, the industry continued to promote beer as “a beverage of moderation.”

Moderation is the taste that stuck as the industry matured during the 20th century. Restrictions on grain use during wartime ruled out the widespread production of hoppy ales in the ’40s, and the palates of a generation of American soldiers grew accustomed to the weak beer that was standard in military rations. These preferences were solidified by massive consolidation of the industry, which took place because only big, national producers could survive in a market with such low profit margins. In 1940, there were 684 breweries. In 1979, there were 44.

The ’70s only made American beer blander. After having tried and failed to launch lite beers in the ’50s, national producers found success two decades later, when fad diets and calorie-consciousness had taken hold.

Why was it, though, that bland beer came to dominate in America, and not in most of Europe? Dighe says there are two reasons. First, those miners and factory workers who preferred light beers had weaker union protections than European workers, who had a bit more leeway when it came to showing up at work tipsy. The other reason, says Dighe, is the “uncommon strength and puritanism of the 19th century American Temperance movement, which, unlike its European counterparts, did not see beer as a temperate alternative to hard liquor.”

Of course, that’s not the end of the story. In the ’70s, anyone whose tastes deviated even a tiny bit from the mainstream had few options outside of homebrewing. Glenn Carroll, a professor at UC Berkeley’s business school, saw that this left an important opening, as he wrote in a 1985 study, “Although it is premature to make predictions, the U.S. market appears ready for an upsurge of specialist breweries.” By relying on a passionate customer base that had no qualms spending a few extra dollars for a fuller-flavored beer, craft breweries could compete in a mass market with low margins. Carroll’s assessment proved prescient: The U.S. had two craft breweries in 1977, and 2,751 in 2012. Dighe predicts that this expansion will only continue, and beer will only become hoppier.

But, lest Jefferson finally rest easy, beer today by and large remains meagre and often vapid: Craft beers only account for about a tenth of the market.

* This article originally stated that early American beers required imported hops. Actually, it was malted barley that needed to be imported, not hops. Malted barley is a partially germinated grain, which primarily determines a beer's color, flavor, and body. Hops contribute a beer's bitterness and aroma. We regret the error.