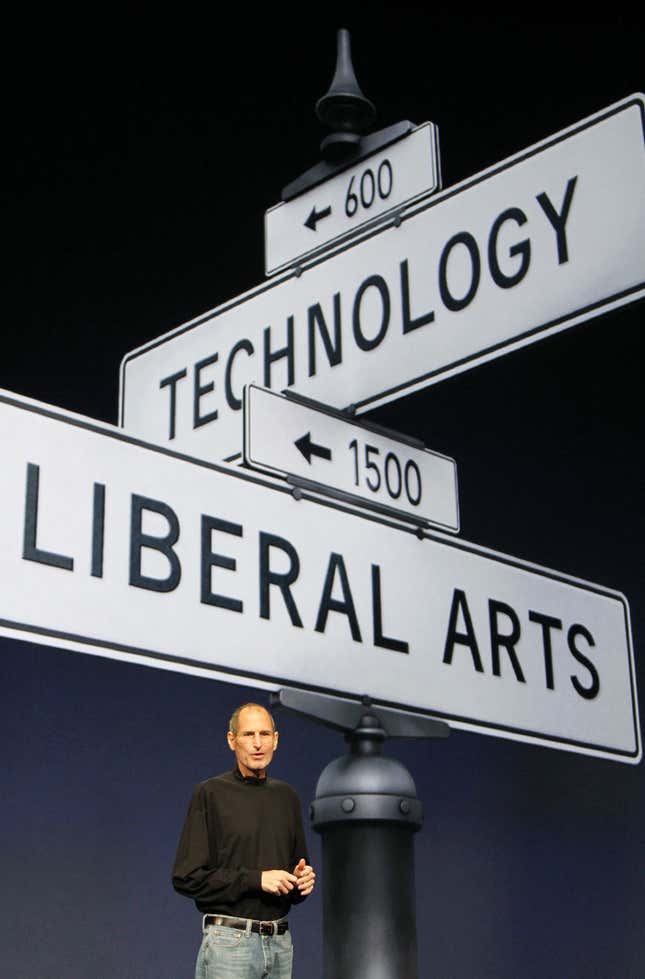

The late Steve Jobs sometimes ended Apple’s product-launch events with a brief, higher-level sermon of sorts. A few times, he showed this slide with two intersecting street signs: “Technology” and “Liberal Arts.”

“It’s in Apple’s DNA that technology alone is not enough,” he said in 2011 after unveiling the iPad 2. “It’s technology married with liberal arts—married with the humanities—that yields us the result that makes our hearts sing.”

In that respect, I think Jobs would have appreciated Apple Music, the company’s new streaming music service, which launched yesterday (June 30) in more than 100 countries.

In broad strokes, Apple Music itself isn’t a revolutionary concept. Like Spotify, Rhapsody, and Rdio before it, Apple Music is an app—a piece of software technology. It offers a large library of music available for streaming, with a selection of playlists and basic social sharing. It has some Apple-specific features that might come in handy, like syncing songs to an Apple Watch for offline access. And in brief testing, it seems to work fine, especially on mobile.

But what makes Apple Music interesting is the “humanities” aspect. And the best, most memorable example so far is Apple’s experiment with radio.

In the age of sterile, algorithmic automation, Apple has launched a high-profile, global radio station—Beats 1—powered by humans with personalities, led by former BBC jock Zane Lowe.

It is broadcast 24 hours a day, with real people picking songs, introducing them, and conducting interviews. Everyone around the globe hears the same thing at the same time—a rarity for internet-based media, which is rarely experienced in sync. As a result, everyone can also discuss in real-time. It’s early, but tuning into Beats 1 on launch day and following along with other listeners on Twitter made it a fun, memorable, shared experience.

“Dedicated 10 years of my life to the idea that everyone should be able to enjoy and discover the music *they love* and without judgment,” former Pandora executive Tom Conrad tweeted shortly after the launch, adding, ”the idea of a 24/7 broadcast station hosted by celebs and tastemakers is pretty much the opposite of that. But I’ll be damned if @zanelowe and @Beats1, at least for me, isn’t a great listen so far.”

And here’s another take from recent internet radio entrepreneur Rex Sorgatz:

Would Jobs have green-lit this approach? The man played The Beatles and Bob Dylan on stage during demos, so it’s tough to say he would care for the current pop selection on Beats 1. But as a booster for old, professionally produced media—and of liberal-arts services designed to complement technology—I like to think he would have appreciated the experience Apple Music is delivering.

Apple’s real goal, anyway, is simply to get more people streaming music. If they enjoy what they’re subscribing to, their iPhones will become all the more valuable to them, increasing the chance they’ll stay loyal.

Some 1 billion smartphones, including 193 million iPhones, were sold last year. Spotify boasts just 75 million active users and 20 million subscribers. For many smartphone owners, Apple Music will be their first streaming service, period.

For it to succeed, the technology will have to come first. (One big question is whether Apple Music is simple enough—Yahoo’s David Pogue, for example, is already complaining that it’s too complicated.) But what makes it interesting is how Apple is bending the boundaries of traditional radio, internet radio, social media, and personal audio to do something different. It might actually work.