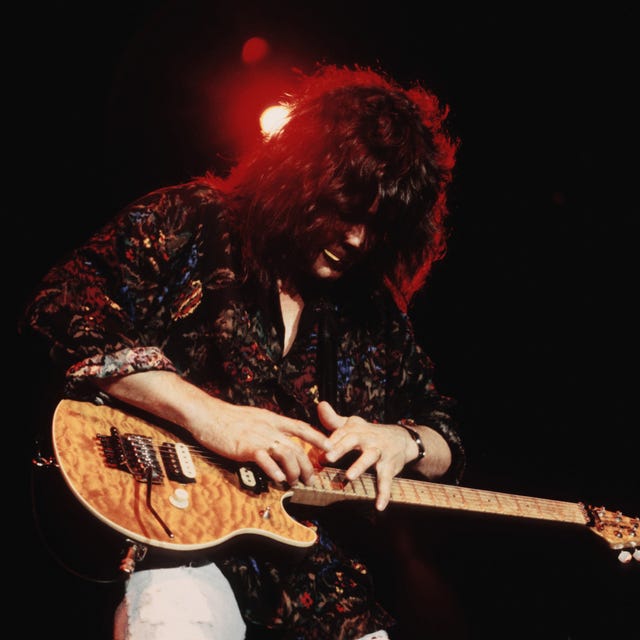

Eddie Van Halen, the legendary guitarist and leader of the pioneering metal band Van Halen, passed away on October 6, 2020 at age 65, after battling cancer. Widely considered to be the greatest guitarist of his generation—and maybe of all time—it isn't a stretch to say the rock god influenced every modern player who came after him. Van Halen's wildly inventive innovations, including tapping, or the act of playing the guitar using both left and right hands on the neck, redefined what musicians could do with the instrument—and what rock and roll music could sound like. Van Halen even patented some of his game-changing techniques.

Van Halen wrote this piece for Popular Mechanics in 2015, discussing his patents, rebuilding his guitars and amps, and searching for his signature sound. To honor him, Pop Mech is reprinting the article in its entirety. May he rest in peace.

I've always been a tinkerer. It comes from my dad. Growing up, we lived in a house in Pasadena that had no driveway. You used an alley that ran through the middle of the block, behind all the houses, to get to your backyard or the garage. Well, the neighbor behind us had a U-Haul trailer up on car jacks and loaded with cinder block.

One night my dad came home from a gig at three in the morning. He had a little heat going, he'd had a few drinks, so he says, "This thing is blocking me from getting in again." So he got out of the car and tried to move it. As soon as he lifted the trailer, the jack fell over, and it chopped his finger off.

➡ You love badass builds. So do we. Let's get our hands dirty together.

This was a problem. Besides the obvious reasons, he played clarinet and saxophone. On a sax, you don't need to seal the hole with your finger. A valve closes over it. But with a clarinet, you have to seal the hole, so he took a saxophone valve cover and adapted it to work on his clarinet.

Another funny thing was later in his life, when he started losing his teeth. You need your bottom teeth to play a reed instrument. Instead of going to the dentist, he made himself a perfectly shaped prosthesis out of white Teflon that filled the gap where his teeth were missing. He slipped that in when he had to play. Watching him do that kind of stuff instilled a curiosity in me. If something doesn't do what you want it to, there's always a way to fix it.

Stock Guitars

My playing style really grew from the fact that I couldn't afford a distortion pedal. I had to try to squeeze those sounds out of my guitar. The first real work I did was in my bedroom. I added pickups, because I didn't like the sound of the originals.

I couldn't afford a router—I didn't even know what a router was—so I started hammering away with a screwdriver. That didn't work at all. Chunks of wood flew off and there was sawdust flying all over the place. But I was on a mission. I knew what I wanted and I just kept at it until I finally got there.

Most guitar necks are too round on the back, so I took sandpaper and reshaped the neck to be very flat. I actually refretted a few guitars early on because I wanted to shave the fingerboard down and make the neck even flatter. The flatter it was, the farther I could bend a string without fretting out, or choking the sound when the string hits a fret higher on the neck.

The other issue, with Fenders, at least, was the clear lacquer they'd put on the neck. When you sweat, your fingers either slide all over the place or get sticky. I couldn't stand that, so when I built my first guitar, I used natural wood. My own sweat and oil would soak in to make it smooth. It took a lot of playing to get it that way but, eventually, it just felt so much better than any synthetic product you could put on there.

The Whammy Bar

Vibrato bars (also called whammy bars or tremolos) just didn't stay in tune. The problem was the nut—the string guides at the end of the guitar neck. On the first album I used a standard, nonlocking Fender tremolo. The string is angled down from the nut to the tuning pegs, creating tension that, after the string slides back and forth when you use the whammy bar, keeps the string from returning to its original slot. I made my own nut with really smooth indentations—big and round like the bottom of a boat. I put a drop of 3-In-One oil in there, too, so the string would be extra slippery.

On top of that, instead of winding the string down on the tuning peg, creating an angle and causing that tension, I would wind it up so that, from the nut all the way back to the bridge, the string was level. Otherwise there could be hangups in the nut that would make the guitar go out of tune when you went crazy on the whammy bar.

The only problem this caused was when you hit an open string, where your fingers aren't holding it down. Without that tension, the string would pop out of the nut slot, so I'd have to remember to put my finger on the far side of the nut to hold things together.

Amps

If it was movable, or turnable, or anything that resembled something that could go up or down, I would mess with it to make the amp run hotter. I opened the amp up and saw this thing. I found out later it was a bias control, which controls the power to the output tubes. I'm poking around, and all of a sudden I touch this huge blue thing and my God, it was like being punched in the chest by Mike Tyson. My whole body flexed stiff, and it must have thrown me five feet. I'd touched a capacitor. I didn't know they held voltage.

The Marshall amp I brought home from the store where I worked was only good if you turned it all the way up. Any lower and you'd lose the distortion. I needed that, but it was impossible to play anywhere with the volume that loud, so I tried everything, from leaving the thick plastic cover on it to facing it backwards to putting it face down. I'd blow a fuse twice an hour.

Luckily, I stumbled onto the Variac transformer soon after. I'd bought another Marshall amp, and I had no idea that it was actually a European model. I plugged it in, and I'm waiting for it to warm up and thinking, I got ripped off here, there's no sound coming out! Pissed off, I came back an hour later to give it another shot.

I'd left the amp on the whole time. I didn't know it was set on 220, so when I turn my guitar on it sounds like a full-blown Marshall, all the way up, except really, really quiet. That was when I realized there was something going on with the voltage. There were these cheesy light dimmers in the house, and I hooked it up to one of those.

Of course I wired it backwards and shorted out the whole house, so I went down to a place in Pasadena and asked if there was some kind of industrial-size variable transformer that would let me adjust voltage, and they introduced me to the Variac. It's just a huge light dimmer. I plugged it into the amp and controlled the voltage from that. That became my volume knob. I would set the voltage depending on the size of the room we were playing, getting all that feedback at any volume.

Pickups

My first real guitar was a Les Paul Goldtop. I was a total Eric Clapton freak, and I saw old pictures of him playing a Les Paul. Except his had humbucking pickups, and mine had the soapbar, P-90 single coils. The first thing I did with that guitar was chisel it out in the back and put a humbucker in. When we were playing gigs, people kept saying, "How is he getting that sound out of single—coil soapbar pickups?" Since my hand was covering the humbucker, they never realized that I'd put it in.

When my guitar was black and white, I cut out my own pickguard so it would cover the holes from the pickup I'd removed. But when I painted red on top of the black and white, which is how it is now, it didn't look cool with that black pickguard. It covered most of the paint job. I decided just to take the switch and cram it in the middle and put a nonworking pickup in the front because I didn't use it. I wasn't trying to trick anyone. Bottom line is, I didn't know how to hook it back up.

The last real step for me was adding paraffin wax to my pickup. Pickups can have this really high-end squeal, like the annoying screech of feedback you sometimes hear when someone speaks into a microphone. I thought maybe what was causing that with a guitar was the coil windings vibrating. So what I did—and I have no idea where this idea came from—was buy a hot plate and bricks of paraffin, and borrow a Yuban coffee can from my mom to put the wax in.

Of course I ruined a lot of pickups, because the plastic frames would melt before I had a chance to yank the pickup out. But finally, when I had a chance to really keep an eye on it, as soon as I saw the pickup start to heat up and shrivel a little bit I'd yank it out.

Man, the first time I put that in—between the Variac, the beast that Marshall was, and now the pickup not having unwanted feedback—the combination was just ideal. That was heaven to me. When all those things came together, it was like, okay, I'm going crazy with the whammy bar, I got my Marshall with the Variac, there's no stopping me.

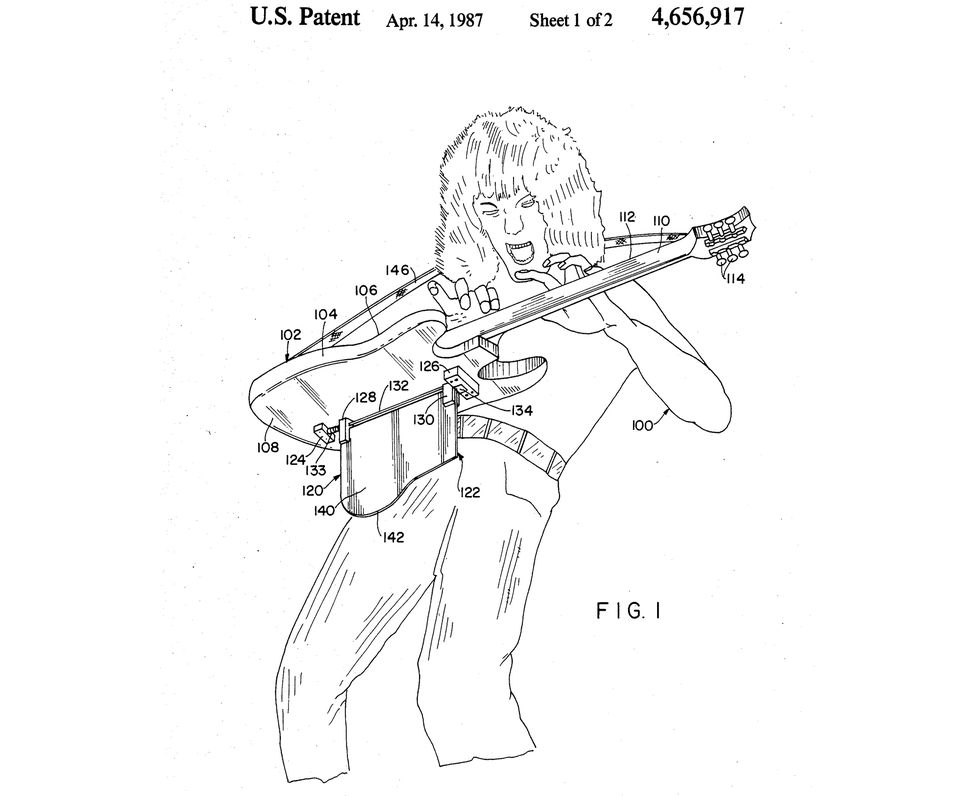

🎸 The Patents of Eddie Van Halen

U.S. Patent #388117. Guitar peghead: Placing the tuning pegs on the opposite sides of the headstocks helps the strings hold tension. It also obviates the need for string trees, guides that clamp down on your strings and hinder string replacement.

U.S. Patent #4656917 Musical instrument support: A bracket that swings down from the back of the guitar, supporting it at a 90-degree angle from your body and letting you play the instrument like a lap guitar.

How to Play Like Eddie

(Or at least look a little more like him when you do play.)

Van Halen started manufacturing his own equipment in 2007 under the brand EVH Gear. His newest offering, the Wolfgang WG Standard, launched in the spring. Named for Van Halen's son, the entry-level guitar is made from extremely lightweight and porous basswood, providing the perfect resonance for musicians who are heavy on the treble and fade. The neck is maple, with a deliberately minimal satin finish.

"The more porous the wood, the more tone you're going to get," Van Halen says. "My guitars aren't sealed, so they breathe. The sap can escape, allowing the wood to age." If you get good enough to really wail, the specialty Floyd Rose bridge locks the strings to the body in two places instead of just one, so the guitar stays in tune, even when you hit a dive bomb—the high-pitched whine at the end of the song that you know you're going to try.