The Federal Communications Commission today voted to enforce net neutrality rules that prevent Internet providers—including cellular carriers—from blocking or throttling traffic or giving priority to Web services in exchange for payment.

“This is no more a plan to regulate the Internet than the First Amendment is a plan to regulate free speech.”

The most controversial part of the FCC's decision reclassifies fixed and mobile broadband as a telecommunications service, with providers to be regulated as common carriers under Title II of the Communications Act. This decision brings Internet service under the same type of regulatory regime faced by wireline telephone service and mobile voice, though the FCC is forbearing from stricter utility-style rules that it could also apply under Title II.

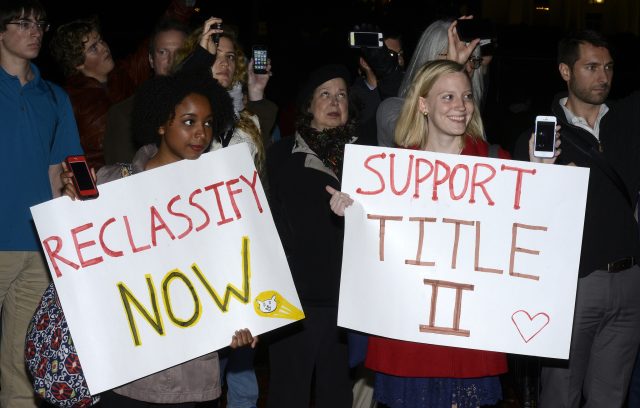

The decision comes after a year of intense public interest, with the FCC receiving four million public comments from companies, trade associations, advocacy groups, and individuals. President Obama weighed in as well, asking the FCC to adopt the rules using Title II as the legal underpinning. The vote was 3-2, with Democrats voting in favor and Republicans against.

Chairman Tom Wheeler said that broadband providers have the technical ability and financial incentive to impose restrictions on the Internet. Wheeler said further:

The Internet is the most powerful and pervasive platform on the planet. It is simply too important to be left without rules and without a referee on the field. Think about it. The Internet has replaced the functions of the telephone and the post office. The Internet has redefined commerce, and as the outpouring from four million Americans has demonstrated, the Internet is the ultimate vehicle for free expression. The Internet is simply too important to allow broadband providers to be the ones making the rules.

This proposal has been described by one opponent as "a secret plan to regulate the Internet." Nonsense. This is no more a plan to regulate the Internet than the First Amendment is a plan to regulate free speech. They both stand for the same concepts: openness, expression, and an absence of gate keepers telling people what they can do, where they can go, and what they can think.

Wheeler also said putting rules in place will give network operators the certainty they need to keep investing.

In May 2014, the Wheeler-led commission proposed rules that relied on weaker authority and did not ban paid fast lanes. Wheeler eventually changed his mind, leading to today's vote.

Commissioner Mignon Clyburn, the longest-tenured commissioner and someone who supported Title II five years ago, said the net neutrality order does not address only theoretical harms.

"This is more than a theoretical exercise," she said. "Providers here in the United States have, in fact, blocked applications on mobile devices, which not only hampers free expression, it also restricts innovation by allowing companies, not the consumer, to pick winners and losers."

Clyburn convinced Chairman Tom Wheeler to remove language that she believed was problematic.

“We worked closely with the chairman's office to strike an appropriate balance and, yes, it is true that significant changes were made at my office's request, including the elimination of the sender side classification, but I firmly believe that these edits have strengthened this item," she said.

Clyburn, Google, and consumer advocacy groups told Wheeler that language classifying a business relationship between ISPs and Web services as a common carrier service could give ISPs grounds to charge online content providers for access to their networks. This language was removed, but service that ISPs offer to home and business Internet users was still reclassified as a common carrier service. FCC officials believe this classification alone gives them power to enforce net neutrality rules and oversee network interconnection disputes that affect consumers.

Internet service providers such as Comcast, AT&T, and Verizon lobbied heavily against the Title II decision and could sue to overturn the rules. But Wheeler believes Title II puts the FCC on stronger legal ground. The FCC previously passed net neutrality rules in 2010, relying on some of its weaker authority, but the rules were largely overturned after a Verizon lawsuit.

By winning that case, Verizon inadvertently opened itself and all other Internet providers up to even stricter rules. The new rules go beyond the net neutrality rules passed in 2010. And this time around, the FCC is applying the rules equally to fixed and mobile broadband, whereas its 2010 rules went easier on Verizon's wireless subsidiary and other cellular companies.

The core net neutrality provisions are bans on blocking and throttling traffic, a ban on paid prioritization, and a requirement to disclose network management practices. Broadband providers will not be allowed to block or degrade access to legal content, applications, services, and non-harmful devices or favor some traffic over others in exchange for payment. There are exceptions for "reasonable network management" and certain data services that don't use the "public Internet." Those include heart monitoring services and the Voice over Internet Protocol services offered by home Internet providers.

The reasonable network management exception applies to blocking and throttling but not paid prioritization.

There are additional Title II requirements that go beyond previous net neutrality rules. There are provisions to investigate consumer complaints, privacy rules, and protections for people with disabilities. Content providers and network operators who connect to ISPs' networks can complain to the FCC about "unjust and unreasonable" interconnection rates and practices. There are also rules guaranteeing ISPs access to poles and other infrastructure controlled by utilities, potentially making it easier to enter new markets. (Republican commissioner Ajit Pai argued that the new rules will actually make cable companies and new providers like Google Fiber pay higher fees for access to utility poles.)

There is also a "general conduct" standard designed to judge whether future activity not contemplated by the order harms end users or online content providers.

The FCC could have tried to use Title II to require last-mile unbundling, in which Internet providers would have to sell wholesale access to their networks. This would allow new competitors to enter local markets without having to build their own infrastructure. But the FCC decided not to impose unbundling. As such, the vote does little to boost Internet service competition in cities or towns. But it's an attempt to prevent incumbent ISPs from using their market dominance to harm online providers, including those who offer services that compete against the broadband providers' voice and video products.

What’s next: Lawsuits and Congressional intervention

Opponents claim the order will bring new taxes and fees on broadband consumers and onerous procedural requirements for providers. But Wheeler says the order will not authorize any new taxes or fees or impose any "burdensome administrative filing requirements or accounting standards."

Broadband providers claim the rules amount to rate regulation because consumers could bring complaints about their bills to the commission, and the FCC could decide that a particular price is unreasonable. But the FCC would not determine any pricing in advance of specific complaints. Even without Title II, the FCC has authority under Section 706 of the Telecommunications Act to impose price caps on broadband, but it hasn't done so.

“The order retains core authority to prevent unjust and unreasonable practices, protect consumers, and support universal service,” Melissa Kirkel, an FCC attorney advisor, told commissioners. “The order makes clear that broadband providers will not be subject to utility-style regulation. This means no unbundling, tariffs, or other forms of rate regulation, and the order does not require broadband providers to contribute to the Universal Service Fund, nor does it impose, suggest, or authorize any new taxes or fees.”

Today's order could face both legal challenges and action from Congress. Republicans have proposed legislation that would eliminate Title II restrictions for broadband providers and vowed that the FCC vote is just the beginning of the debate.

Although many ISPs publicly oppose the new rules, the industry is by no means united against the FCC. Sprint and T-Mobile US have each said the FCC's proposal would not hurt their business. And while a good number of small broadband providers oppose the imposition of Title II rules, others support Wheeler. The NTCA Rural Broadband Association, which represents rural ISPs, said yesterday that it supports applying Title II to broadband networks.

Sir Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web, spoke to the commission via video. He credited the openness of the Internet with allowing him to create the Web 25 years ago without having to ask "permission."

Republican Commissioner Michael O'Rielly dissented, accusing Wheeler of bowing to Obama's wishes. O'Rielly's written statement said:

Let me start by issuing apologies. First, I am just sick about what Chairman Wheeler was forced to go through during this process. It was disgraceful to have the Administration overtake the commission’s rulemaking process and dictate an outcome for pure political purposes. It is so disturbing to know that those efforts were about illegitimately pushing a larger political cause mostly unrelated to technology. This administration went so far beyond what has ever been attempted, and its inappropriate interference in the commission’s activities will forever change this institution.

Additionally, I am sorry to the staff members that were forced to prepare a half-baked, illogical, internally inconsistent, and indefensible document. For an institution that prides itself on quality of work and legal and technical expertise, this document is anything but. I guess that an artificial deadline to meet the radical protestors’ demands means that it is more likely that this item gets overturned by the courts because the work and thoughtful analysis needed to actually defend this completely flawed agenda is not included in the text.

Today, a majority of the commission attempts to usurp the authority of Congress by re-writing the Communications Act to suit its own “values” and political ends.

O'Rielly did not recite the first two paragraphs while reading his statement during the meeting.

Some entrepreneurs spoke in front of the commission. Veena Sud, a writer, director, and producer who developed the TV show The Killing, said the show "survived two near deaths" because of the Open Internet. "When AMC canceled us yet again, Netflix took over the show in its entirety and we were able to end the series as it was intended, all because the Internet was opened up to competition and widened the playing field."

FCC Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel said, "We cannot have a two-tiered Internet with fast lanes that speed the traffic of the privileged and leave the rest of us lagging behind. We cannot have gatekeepers who tell us what we can and cannot do and where we can and cannot go online, and we do not need blocking, throttling, or paid prioritization schemes that undermine the Internet as we know it."

Pai said the FCC is replacing Internet freedom with "government control." The FCC is seizing unilateral authority to regulate Internet conduct and determine what service plans are available to consumers, he said.

"The Internet is not broken. There is no problem for the government to solve," he said.

Pai claimed that an Internet provider could "find itself in the FCC's crosshairs" if it doesn't want to offer unlimited data plans. The FCC's order does not actually ban data caps; instead, the FCC is claiming authority to intervene when companies use data caps to harm competitors or customers.

Pai said the FCC is only deferring a decision on new Universal Service fees for broadband rather than ruling them out entirely. Universal Service fees, which fund telecommunications projects in rural and under-served regions, currently apply to phone bills but not Internet service.

The full net neutrality order has not been published yet. The FCC's majority is required to include the Republicans' dissents in the order and "be responsive to those dissents," Wheeler said. The order will go on the FCC's website after that process. The rules will go into effect 60 days after publication in the Federal Register, with one small exception. Enhancements to the transparency rule must undergo an additional review by the Office of Management and Budget to comply with the Paperwork Reduction Act.

reader comments

666