The Surprisingly Short History of the Pony Express

Given that most have still heard of the Pony Express today, unlike so many other messaging companies long gone, you may think that the Pony Express was once an integral part of communication between the East and West in the United States. It turns out, this was never the case and the Pony Express was around only for an extremely short amount of time.

It all started on April 3, 1860, when two riders, one in Sacramento, California, the other in St. Joseph, Missouri, simultaneously embarked on a mirror-like mission – carry mail across the difficult and dangerous terrain of the American West in the shortest amount of time possible. With each load (including the riders) weighing no more than 165 pounds, the two men reached the others’ starting point in record time: the westbound rider made it to Sacramento in just under 10 days, while the eastbound man reached St. Joseph in 11.5. Together, these journeys marked the beginning of the Pony Express.

The brainchild of visionary businessman William Russell, the Leavenworth & Pike’s Peak Express Company (later to be known as the Pony Express) was born of two desires: (1) people’s need to communicate and (2) a businessman’s need for profit.

By the 1850s, hundreds of thousands of Americans had migrated to live west of the Rocky Mountains. Remember that by this time, California had seen its great Gold Rush, the Mormons had fled religious persecution and were settling in Utah in large numbers, and thousands of pioneers had made the arduous trek of the Oregon Trail over the high mountains to homestead in the West.

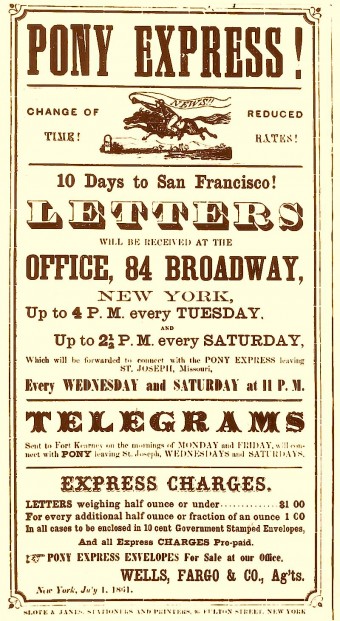

Before the Pony Express, it could take up to 8 weeks for a letter from the eastern U.S. to reach these westerners since most mail was shipped by boat. The few letters that went overland only cut that time by half, and then only by taking a southern route for mail service – out of Fort Smith, Arkansas, with stops in El Paso, Texas, and Yuma, Arizona, before arriving in San Francisco, California, three to four weeks later. As you can imagine, anyone who had a need for transcontinental communication was soon frustrated by the extraordinarily long delivery time, and just as long for a reply.

Coinciding with the national desire for speedier mail service was Russell’s need for a new source of income. Together with his partners, William Bradford and Alexander Majors, Russell ran a stage coach and freight business out of Leavenworth, Kansas that by the late 1850s was floundering. While on a trip to Washington, he pitched an idea to California’s Senator William Gwin – to quickly deliver mail via an overland central route that followed the Oregon and California trails.

The key to his speedy delivery was to be a system of hundreds of way stations where fresh horses and riders would be continuously substituted all along the 1,800 mile trail. The route itself began in St. Joseph, Missouri, followed the Platte and Sweetwater rivers, then crossed the Rockies via the South Pass to Salt Lake City, Utah. From there, the riders crossed the deserts of Utah and Nevada, then went over the Sierra Nevada Mountains and finally landed in California – all in about 10 days.

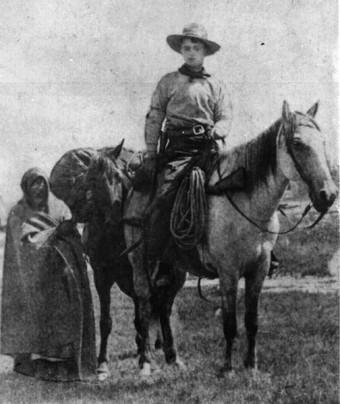

Hundreds of men were hired to manage the way stations where fresh horses (between 400 and 500 total) and riders (about 80) would be waiting to relieve a tired courier. The riders themselves had to be small, under 120 pounds, and the mail bags were limited to 20 pounds, all to keep the weight the horses had to bear to a minimum (which, with equipment and mail, was capped at 165 pounds).

The couriers, who were paid $25 per week (about $640 today), were given a distinctive uniform of red shirt and blue pants, and at first, they blew a brass horn to signal their impending arrival at a way station. This last was soon discarded, however, when it became clear that the approaching hoof beats provided sufficient notice.

The couriers, who were paid $25 per week (about $640 today), were given a distinctive uniform of red shirt and blue pants, and at first, they blew a brass horn to signal their impending arrival at a way station. This last was soon discarded, however, when it became clear that the approaching hoof beats provided sufficient notice.

For maximum efficiency, a station was placed every 10-15 miles for the riders to switch horses, and then after every 75-100 miles, the couriers themselves would be replaced.

The enterprise was intended to make a profit, and Russell and his partners had hoped Uncle Sam would ultimately subsidize the venture. It didn’t, and even though the Express initially charged $5 per half-ounce of mail (today’s U.S. Post Office charges $0.49 for up to 13 ounces for first class delivery), the Pony Express operated at a significant loss.

Its end came quickly – just 19 months after it started, when it was replaced with better technology. Beginning in June 1860 (only two months after the first Pony Express ride), telegraph lines to connect the East and West Coasts were begun by the Pacific Telegraph Company coming out of Nebraska and the Overland Telegraph Company from California. On October 24, 1861, the transcontinental telegraph was up and running and two days later, the Pony Express officially ended. A great idea, but bad timing.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Difference Between a Pony and a Horse

- The Horses of World War I

- The Origin of the Term “Going Postal”

- “Billy the Kid’s” Real Name was Not William H. Bonney

- The U.S. Army’s Camel Corps

Bonus Facts:

- Though not called spam back then, telegraphic spam messages (see How the Word Spam Came to Mean Junk Mail) were extremely common in the 19th century in the United States particularly. Western Union allowed telegraphic messages on its network to be sent to multiple destinations. Thus, wealthy American residents tended to get numerous spam messages through telegrams presenting unsolicited investment offers and the like. This wasn’t nearly as much of a problem in Europe due to the fact that telegraphy was regulated by post offices in Europe.

- Buffalo Bill Cody (1846-1917) was a Pony Express rider. Outside of riding for the Pony Express, he is estimated to have killed around 20,000 bison (often called “Buffalo,” even though they are not) in his lifetime. For reference, one single hide in good condition would bring in about $3. Made into a winter coat, it could bring in as much as $50. Ironically, Buffalo Bill was one of the most outspoken supporters of plans to protect the bison populations through legislation. In the end, President Grant vetoed the bill that would have protected the herds, due to the frequent small wars the U.S. had to fight with the Plains Indians. By getting rid of the bison herds, it took away the Plains Indians primary food and clothing source.

- A common myth surrounding American Bison is that there were massive herds before the “white man” came to America, on the scale that Americans eventually encountered them at. In fact, evidence suggests that the Native Americans kept the bison populations regulated by various means. After the European diseases wiped out most of the Native Americans, the American Bison population exploded, becoming the most numerous large wild mammal on Earth until eventually hunted to near extinction within a few centuries after this population explosion. At their peak, it was estimated that there were nearly 100 million American Bison in existence, only a few centuries ago.

- Before horses and guns were introduced to Native Americans, hunting bison was a dangerous affair, with the bison being extremely aggressive and hard to kill. One of the methods of hunting them that the Native Americans would use was to attempt to herd a large group of bison into chutes of rock, which lead to a drop-off. They’d then incite a stampede with much of the herd falling to their deaths. The meat and skins could then be easily gathered.

- The fastest delivery every made by the Pony Express was President Lincoln’s inauguration address that was delivered in less than 8 days.

- The first telegram sent, on May 26, 1844, was from Samuel Morse (who invented the code) and read, “What Hath God Wrought?”

- The last Western Union telegram was sent in the U.S. on January 27, 2006, and in India the Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd. sent its last telegram on or about July 14, 2013.

- The famous use of “stop” instead of a period was due to the fact that it cost extra for a “.” but the four letter word “stop” was free.

- The shortest telegrams possible were reportedly sent between either Oscar Wilde or Victor Hugo and the writer’s publisher. Asking of the status of sales of his latest novel, the author is said to have sent “?” while the publisher is to have replied “!”

- The day telegrams came to a final STOP

- First Transcontinental Telegraph System Was Completed

- The Gold Rush of 1849

- History of the Pony Express

- India sends its last telegram. Stop.

- Mormons begin exodus in Utah

- Pony Express

- Pony Express Debuts

- Pony Express History

- Story of the Pony Express Trail

- Telegram Falls Silent Stop Era Ends Stop

- A thousand pioneers head West on the Oregon Trail

- Western Union sends last telegram

- William F. Cody

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

“[T]oday’s U.S. Post Office charges $0.49 for up to 13 ounces for first class delivery…” Really? I’m missed that! How does one send 13 oz for the one-ounce rate? I know first-class mail cannot exceed 13 oz in weight, but I thought the /rate/ for 13 oz was $3.50 for flats and $4.12 for parcels.