In a Capitol Hill hearing room two summers ago, privacy activist Christopher Soghoian organized a stunning demonstration of some new police surveillance technology. A small group of congressional staffers were handed "clean" cellphones and invited to start calling each other while, off to the side, a Berkeley communications researcher named Kurtis Heimerl turned on his gear. After a few minutes, Soghoian told the staffers to hang up—and then Heimerl played back their conversations. Not only that, the two men told the staffers, the digital eavesdropping equipment was capable of sucking all the data from their phones—emails, contact files, music, videos—whatever was on them.

Since then, reports that federal, state and local law enforcement agencies are using such devices to track suspects and criminals without warrants have percolated in the national media, thanks largely to Soghoian, now the American Civil Liberties Union's top technologist on privacy issues. (A federal appeals court ruled June 11 that the Fourth Amendment protects people from such intrusions.) Far less well known is the use of such technology by foreign intelligence services against U.S. targets in Washington, D.C., sometimes using criminal go-betweens.

It's a spy war that Q, James Bond's fictional techno-wizard, would envy. Instead of Walther PPK's and Aston Martins, the weapons are silent devices that capture cellphone signals. On one side are the world's major spy services, including those of China, Russia, Israel, France and now Iran. Arrayed against them are technical teams from the FBI and U.S. Secret Service, backed up by the NSA and the CIA.

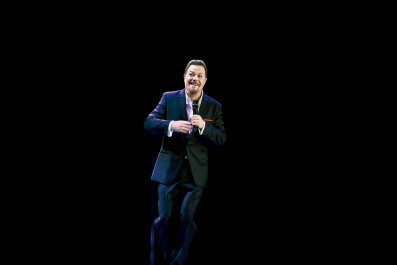

The bad guys may be winning this war, says Soghoian, a ponytailed, British-American former hacker with a Ph.D. from Indiana University. Intelligence officials worry that he's right, but won't say so publicly. And the feds don't want U.S. citizens to know about the technology, critics say, because they are shielding their use of similar devices, the most prominent of which is the StingRay.

Spies With Big Ears

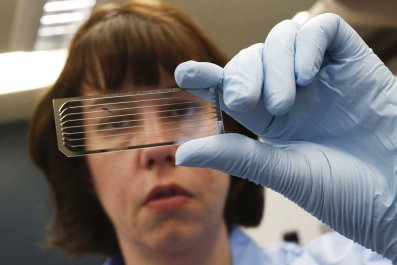

Call it the "IMSI catcher" war, with the acronym standing for International Mobile Subscriber Identity. Every device that communicates with a cell tower—mobile phone, smartphone or tablet—has one. What StingRay (manufactured by Florida-based Harris Corp.) and its competitors do is act like a cellphone tower, drawing the unique IMSI signals into their grasp. Once the device is locked onto a signal, the quarry's data is ripe for the plucking. Major targets include people working for U.S. national security agencies, defense contractors and officials, including members of such congressional panels as the armed services and intelligence committees.

"This type of technology has been used in the past by foreign intelligence agencies here and abroad to target Americans, both [in the] U.S. government and corporations," former FBI deputy director Tim Murphy tells Newsweek. "There's no doubt in my mind that they're using it."

Mike Janke, a former Navy SEAL and co-founder of Silent Circle, a company that sells state-of-the-art encryption software, says, "Defense firms in the Washington, D.C. area have found IMSI catchers attached to the light poles in their parking lots. In February, one or two were found in the parking lot of a defense contractor near Washington."

He adds, "They've also been found in Palo Alto," the capital of Silicon Valley. "The FBI has been called in, but you can't track who has made it."

Keith Flannigan, who has worked for decades in law enforcement as a technical surveillance specialist, says high-tech criminal hackers, mostly in Europe, sell the information to interested parties, including spy services. Such transactions make it easier for the buyers to hide. "That is why," he says of the many cases in which hacking has been detected, "we don't know who the real ones are" behind an electro-heist. "They are smart enough to hire professionals to ensure that they don't get caught."

According to security experts, the main actors in electro-spying on U.S. targets are "the big three"—China, Russia and Israel, the countries fingered by the CIA in a 2013 CIA National Intelligence Estimate on cyberthreats. Janke says Iran has also become a sophisticated player. According to a 2011 report in The Washington Post, Iran-backed Hezbollah used "cellphone records and calling patterns" to bust a CIA spy ring in Beirut.

"It's a cat-and-mouse game," says Janke, a covert communications expert who "has led and coordinated highly classified missions worldwide," according to Silent Circle's website. But it has "tremendous implications," says James Bernazzani, who once headed the FBI's Hezbollah-tracking counterterrorism unit, partly because StingRay "technology can defeat standard encryption." To further complicate the electro-battlefield, there are also devices on the market that each side can use to detect when StingRays are aimed at them.

"Technological advances are most dangerous when the adversary puts 'the good guys' in a reactive and defensive position," Bernazzani told Newsweek. "Technological advances need to stay ahead of those who wish us harm. That is critical."

As in all spy wars, street-level electro-espionage and counterespionage operations are largely invisible. In a rare exposure in 1998, a Russian diplomat was caught eavesdropping on the State Department's C Street headquarters. When the bust was announced, no mention was made of the technology involved, but a former CIA expert tells Newsweek the Russian was wearing "a wired-up body vest" that turned him into a walking, driving antenna nest.

If stories like that conjure up black-and-white images of Nazi radio trucks cruising the dark streets of Paris in search of French Resistance agents, you're not far off, espionage veterans say. "The tech officers [of foreign spy services] are always on the prowl for access points where [communications] can be secretly intercepted or sent, and that's why the opposition's tech officer's movements are of particular interest to [U.S. government] surveillance," the former CIA man says. "It's rare that technical operations get exposed, since they're so carefully planned and executed."

The electro-war is "3-D—in the air, underwater, in buildings, underground," the ex-spy explains. "A tech team in a van may be targeting a U.S. official's cellphone inside a restaurant and turning on the microphone remotely. Or they may be tracking a target whose car has a beacon.

"Traditionally, the main base of…technical ops is from an embassy, consulate or military base," he adds. "It's sovereign territory and safe.… The Russian Embassy, up on the hill overlooking Georgetown, has an ideal location to grab signals. Israel's embassy is next door to Intelsat," which operates over 50 communications satellites for U.S. and foreign clients. The Chinese Consulate in Tijuana, Mexico, has great electro-coverage of Southern California, according to the U.S. government's Intelligence Threat Handbook.

It's Everywhere Now

Thanks to Edward Snowden's snooping disclosures about the National Security Agency, we all know that the U.S. is listening too, mostly from the air-conditioned comfort of the NSA's headquarters in Fort Meade, Maryland, or in American embassies. According to a recent piece by intelligence expert Matthew Aid in Foreign Policy magazine, the FBI attaches StingRay-like devices to helicopters and flies them over foreign embassies in Washington.

That's a breeze compared with electro-spy vs. spy ops on the ground. "Technical operations can get very complex and high-risk when it comes to involving the human factor and street work," the CIA veteran says. "When case officers"—jargon for spy handlers—"join with tech officers and local agents, the intel wars take on a high-risk flavor."

Harris Corp. is no longer the sole source for IMSI catchers. Judging by the catalog of SafeTech, a Brazilian dealer in high-end police equipment, obtained by Newsweek, StingRays and associated equipment are easily available worldwide. (The company does not comment on its sales.) Meanwhile, foreign manufacturers have developed their own versions.

"There are several others [on the market]," says Flannigan, director of International Dynamics Research Corp., a Virginia company that offers technical surveillance countermeasures training to private and government clients in the U.S. and abroad. "There is a much better unit that is totally undetectable, that is good for about 1 ½ miles, that will record and resend all cell activity in that area." One leading manufacturer is an Israeli company, Ability, which, according to its website, was "founded in 1993 by a team of experts in military intelligence and communications, who were joined by specialists in electronics and mathematics…to devise state of the art encryption and decryption solutions…to security and intelligence agencies, military forces, police and homeland security services around the world."

"The sword cuts both ways," says Murphy, who worked in technical, undercover and surveillance operations during his FBI career. "As we advance in technology, the bad guys advance in technology, too. You're seeing that in the cyberwars.… The tools are easy to get ahold of. They're cheaper and faster, and the availability is widespread. So it wouldn't surprise me that adversarial, state-sponsored activity is going on and targeting our individuals, and at an exponential rate."

It's everywhere now, experts say. Stalkers have it. Private eyes have it. Tabloid reporters could have it (if they want to risk getting busted like Rupert Murdoch's British cellphone snoopers). Surely political "opposition researchers" have it. Nobody's iPhone or iPad is safe from the IMSI catchers.

In the wake of a 1996 incident in which a Florida couple "accidentally" eavesdropped on a conference call between key Republicans, including Newt Gingrich and future House Speaker John Boehner, federal legislation was passed to protect analog communications from interception.

It didn't work. And obviously, the tech world has moved far beyond those primitive devices, privacy activists argue. In a paper to be published later this year in the Harvard Journal of Law & Technology, Soghoian and Stephanie K. Pell, a former federal prosecutor who served as counsel to the assistant attorney general of the Justice Department's National Security Division, argue that "policy makers did not learn the right lessons from the analog cellular interception vulnerabilities of the '90s.… "[The] communications of Americans will only be secured through the use of privacy enhancing technologies like encryption," they write, "not with regulations prohibiting the use or sale of interception technology."

Try getting government officials to even talk about the need for higher encryption standards. "In spite of the security threat posed by foreign government and criminal use of cellular interception technology," Soghoian and Pell write, "U.S. government agencies continue to treat practically everything about it as a closely guarded 'source and method'"—jargon for intelligence tradecraft protected from public disclosure—"shrouding the technical capabilities, limitations and even the name of the equipment they use from public disclosure."

Indeed, the FBI, Secret Service and Department of Homeland Security all declined to comment on the security threat for Newsweek. A spokesman for the State Department said only, "We provide briefings to our diplomats on the vulnerabilities of using cellphones and telephones while serving overseas," which includes reminders of "the risks associated with revealing personal information via telephones or cellular phones."

The main feature of StingRays and the like is that one need not say anything on a cellphone to serve up valuable information. Once such devices suck data from your machine, they can find you (and your stored contacts) anywhere—even when your phone is turned off.

U.S. law enforcement and spy agencies, which make extensive use of StingRays and countermeasures, refuse to talk about the security threat, especially in a public forum.

Soghoian says that after his demonstration in the congressional hearing room two summers ago, "the staff were pretty shocked…but nothing happened after.

"No hearings, no letters, nada."

Jeff Stein writes SpyTalk from Washington, D.C. He can be reached via encrypted email at spytalk[at]hushmail.com.